It's peculiar that I had lived in Yellowstone for so many years before I ever caught Tower Fall at the right time of day for this scene: the massive spray from the waterfall backlit by strong sunlight, filling the entire canyon with a dazzling light. I have this scene in both slides and born-digital images and may have to scan one of the slides someday for comparison.

Tower Fall is a fine example of a hanging creek, a small river that's cutting downward as fast as it can, but just can't keep up with the more powerful and erosive river that it empties into. In this case, Tower Creek has to drop 132 feet in order to catch up with the mighty Yellowstone River just a couple hundred yards away. Multnomah Falls near Portland, Oregon, is an especially spectacular example, if you happen to be going that way.

The creek and waterfall were named by the members of the Washburn expedition of 1870 early in their explorations. In his account of the expedition, Nathanial Langford added this footnote to the story of the naming of Tower Fall:

At the outset of our journey we had agreed that we would not give to any object of interest which we might discover the name of any of our party nor of our friends. This rule was to be religiously observed. While in camp Sunday, August 28th, on the bank of this creek, it was suggested that we select a name for the creek and fall. Walter Trumbull suggested "Minaret Creek" and "Minaret Fall." Mr. Hauser suggested "Tower Creek" and "Tower Fall." After some discussion a vote was taken, and by a small majority the name "Minaret" was decided upon. During the following evening Mr. Hauser stated with great seriousness that we had violated our agreement made relative to naming objects for our friends. He said that the well known Southern family -- the Rhetts -- lived in St. Louis, and that they had a most charming and accomplished daughter named "Minnie." He said that this daughter was a sweetheart of Mr. Trumbull. Mr. Trumbull indignantly denied the truth of Hauser's statement, and Hauser as determinedly insisted that it was the truth, and the vote was therefore reconsidered, and by a substantial majority it was decided to substitute "Tower" for "Minaret." Later, and when it was too late to recall or reverse the action of our party, it was surmised that Hauser himself had a sweetheart in St. Louis, a Miss Tower. Some of our party, Walter Trumbull especially, always insisted that such was the case. The weight of testimony was so evenly balanced that I shall hesitate long before I believe either side of this part of the story.

Given Nathanial Langford's track record with campfire stories, I wouldn't hesitate an instant before disbelieving every side of this part of the story. His tale of the origin of the national park idea, that the party was camped at the confluence of the Firehole and Gibbon Rivers (to form the Madison) discussing the profits to be made from claiming the areas around the waterfalls and geysers under the Homestead Acts and charging tourists to see them, when one of his companions solemnly declared that they should reject such base scheming and work to have the area given over to the people as a national park -- well, that story has long been debunked, with a corresponding decline in Langford's reputation as a scrupulous man.

In any event, Walter Trumbull ended up marrying a woman named Slater, while Samuel Hauser married one Helen Farrar only a year after this supposed campfire spat. You'd have thought naming a waterfall in the first national park after your lover would earn you a few more boyfriend points than that, but women are fickle, I suppose. Neither man ever managed to marry a Miss Tower or Miss Rhett.

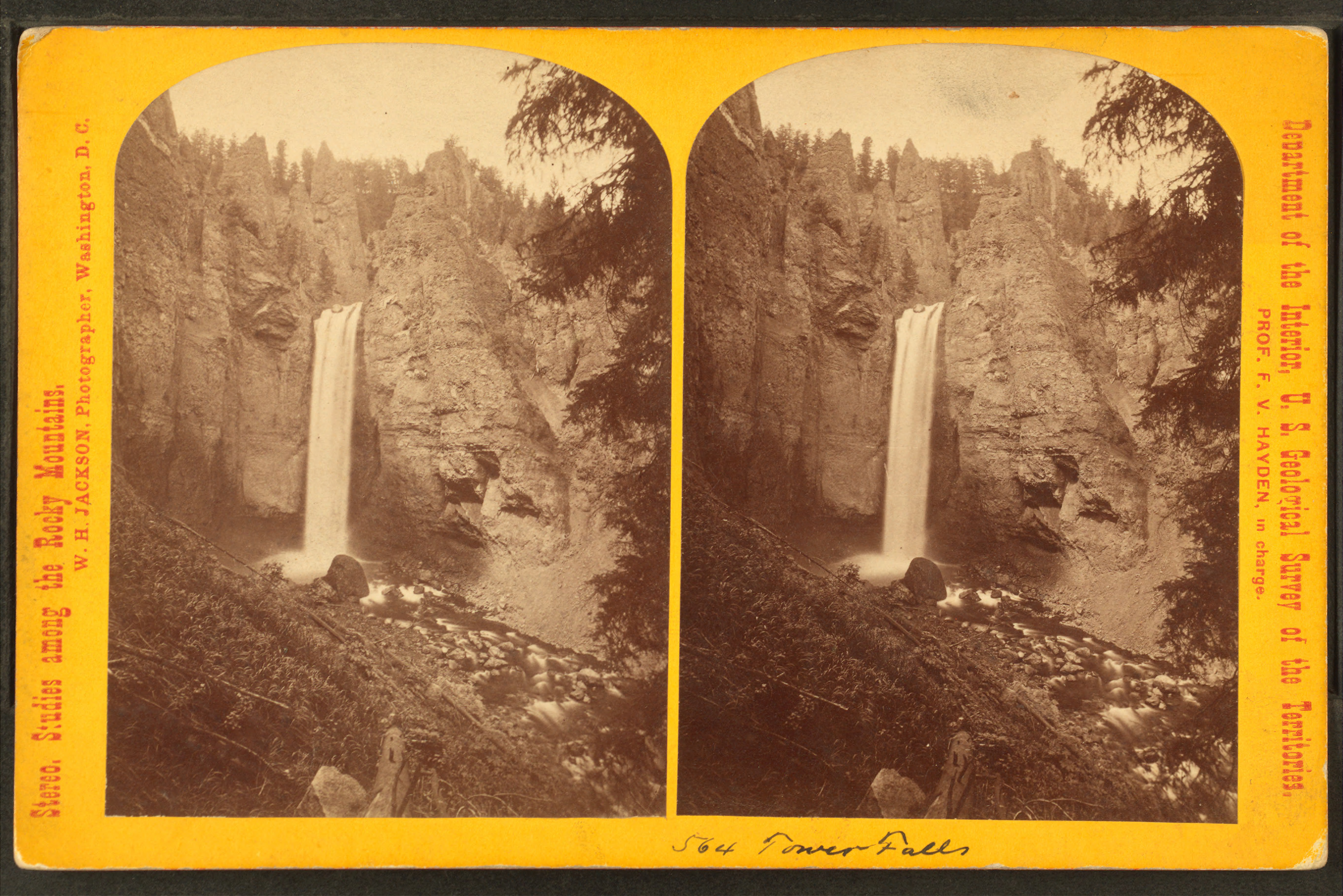

This William Henry Jackson photo nicely illustrates why "Minaret" would have been an entirely appropriate name for this waterfall. The sketch below was made by one of the soldiers on the Washburn expedition and, as far as us white folks go, is certainly the very earliest pictorial representation of Tower Fall.

This William Henry Jackson photo nicely illustrates why "Minaret" would have been an entirely appropriate name for this waterfall. The sketch below was made by one of the soldiers on the Washburn expedition and, as far as us white folks go, is certainly the very earliest pictorial representation of Tower Fall.

By the way, if you click on the Jackson photo and look closely, you'll spot a small boulder perched precariously on the edge of the waterfall. For over a hundred years, tourists enjoyed speculating on how long it could stay there; it looked like it should fall any minute, but maybe it would last another century, or two, or three? Well, it didn't. Spring floods knocked it off the edge in 1985 or 1986, shortly before I first laid eyes on Tower myself. Alas.

No comments:

Post a Comment