A month ago a hiker was killed by a grizzly bear in Yellowstone; nothing was done against the bear. Monday the Park Service killed a different grizzly bear that had charged a man and taken the food in his backpack.

The difference? The first bear appears to have been doing nothing but protecting her cubs (a misjudgment, but an understandable one). That sort of behavior doesn't indicate that the bear is any more likely to attack another hiker than any other bear.

The second one, however, seems to have figured out that hikers carry food and that you can get it from them (rather easily, in fact, if you're a bear). Its chances of challenging the next hiker he comes across, and even seeking out the trails where hikers can be found? They might be rather high, which makes this bear far more dangerous than the iconic "mama grizzly." So the bear was destroyed, even though no one had been killed -- yet. Thus confirming the dictum that "a fed bear is a dead bear."

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

(Bear) death in Yellowstone

Labels:

wildlife,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, July 8, 2011

Death in Yellowstone

I missed this story a couple days ago, but a hiker was killed by a grizzly bear east of Canyon Wednesday. He and his wife had the bad luck to surprise a bear with cubs, who charged the pair and fatally mauled the man. The Park Service plans no action against the bear, since it seems to have been acting only in perceived self-defense and has no history of aggression against people.

It's only the sixth documented fatality from a grizzly bear in Park history, and the first since two killings in 1984 in 1986 (although perhaps one should also count the death that occurred just outside the arbitrary Park boundary last summer). Both of those victims were hiking alone in bear country, just as I always did. In '84, a Swiss woman died in her tent after taking all proper precautions; Pelican Valley, where she was camping, has been closed to overnight travel ever since. Two years later, a wildlife photographer was killed and devoured by a grizzly near Otter Creek, south of Canyon. His tripod held a camera with a wide-angle lens mounted on it, indicating that he probably made a choice to approach too close to the bear that killed him.1

____________________________________________________________

1. Whittlesey, Lee. Death in Yellowstone, 1995.

Labels:

wildlife,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, July 1, 2011

Friday photo

Rainbows. The only cheaper subject for a nature photographer is sunsets, and that only because they happen to you more frequently. You get especially spoiled living in the mountains, because unlike the Midwest, where the clouds may cover the entire sky for hours on end, a sharp end to the storm is likely to arrive while the rain is still falling. Also, thunderstorms are especially common in late afternoon and when the cloud's edge approaches, the sun is sinking down to the optimal level for creating rainbows (a 42° angle from sun to rainbow to observer).

As far as the mythology of rainbows goes, I'm mostly familiar with the Noah story, where God promises never again to destroy the Earth with a technique that could never have worked in the first place. You can read a quick summary of some alternative mythologies at the relevant Wikipedia article. I often wonder how much anyone took these stories seriously; after all, we all still know the myth of leprechaun's gold at the end of the rainbow, although people who believe it are probably as scarce today leprechauns. Were these stories ever for the adults, or were they always meant as children's entertainment?

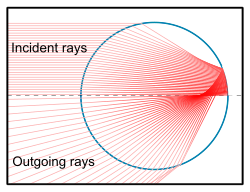

Still, I was a bit surprised to learn how long ago people were trying to figure out how rainbows work, from a naturalistic framework. Based only on surviving writings, we can push it back at least as far as Aristotle in the 4th century BCE. It was probably easy enough to understand that the sunlight was being reflected back from water droplets in the air, since the rainbow always appears in the opposite direction from the sun and, in fact, you don't even need rain. The spray from a waterfall will do nicely. But the Greeks were also damned good with geometry, and Aristotle used these skills to explain how logical it was that that the rainbow should have such a perfect semicircular shape. He grasped that the light had to be reflected at a particular angle back to the observer and that the entire set of points that satisfy this condition would form a circle.*

Figuring out why their are colors is pretty tricky, but sometime around 1300 the Persian astronomer Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī used a large, spherical globe filled with water to model a raindrop and worked out that the ray of light is refracted twice, once as it enters the droplet and again as it leaves, having bounced off the far interior wall. He eventually concluded that the white light was somehow being decomposed into the various colors, anticipating Isaac Newton's famous prism experiments in the 1680's

Figuring out why their are colors is pretty tricky, but sometime around 1300 the Persian astronomer Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī used a large, spherical globe filled with water to model a raindrop and worked out that the ray of light is refracted twice, once as it enters the droplet and again as it leaves, having bounced off the far interior wall. He eventually concluded that the white light was somehow being decomposed into the various colors, anticipating Isaac Newton's famous prism experiments in the 1680's Traditionally, we divide a rainbow into seven colors, but those bands don't really exist and Roy G. Biv is as fictional as Cupid. The bending of the light is seamless and the change in colors ought to appear perfectly seamless as well. But we don't see color that way. We have three types of photoreceptor cone cells in our eyes that each respond to a different wavelength and what we see is a calculation based on those three inputs. Birds, reptiles, and amphibians, on the other hand, have four or five different types of cones and almost certainly can discriminate colors far better than we can. Set your monitor to 256 colors and take off your glasses - that's probably how a bird would feel if you were to suddenly give them human vision.

Traditionally, we divide a rainbow into seven colors, but those bands don't really exist and Roy G. Biv is as fictional as Cupid. The bending of the light is seamless and the change in colors ought to appear perfectly seamless as well. But we don't see color that way. We have three types of photoreceptor cone cells in our eyes that each respond to a different wavelength and what we see is a calculation based on those three inputs. Birds, reptiles, and amphibians, on the other hand, have four or five different types of cones and almost certainly can discriminate colors far better than we can. Set your monitor to 256 colors and take off your glasses - that's probably how a bird would feel if you were to suddenly give them human vision._________________________________________________

* The ground cuts off the bottom half of the circle, of course, but full circle rainbows can be seen from the air. I have a cousin who flew on helicopter gunships in Vietnam and tells me that he saw one. I could really envy him the experience, if it weren't for all that war and shooting and danger business that went along with it.

Labels:

history,

photography,

science,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, June 3, 2011

Friday photo

Here's a nice little view of Mammoth Hot Springs, the headquarters for Yellowstone National Park. It's just inside the northern boundary, 50 miles from Old Faithful and even farther from the more remote reaches of the park; it was selected more for its convenience to the outside world than to the rest of the park. The first government building1 in Yellowstone was a blockhouse built in 1879 on Capitol Hill (the slope you see extending out of the upper right of the frame in the photo); the superintendent was still worried about the possibility of Indian raids (the Nez Perce, fleeing the US Army, had come through just a couple years previously and had killed a couple of tourists).

The red-roofed buildings in the distance are stone officer's barracks from the Fort Yellowstone days, when Yellowstone was an army post between 1886 and 1918. The US Army had been given control over the park after understaffed civilian administration failed to prevent poaching and other destruction. By all accounts, the Army did a commendable job, policing the tourists effectively and reducing poaching to levels that the wildlife could survive.

Those officer's barracks are still in use, most of them serving as residences, while the one nearest the main road is now the Visitors Center. The cottonwood trees lining Officer's Row were planted with, shall we say, military precision: they form a perfectly straight line from one end to the other. That flat area between Capitol Hill and the yellow hotel and restaurant on the left was a parade ground for the cavalry troop stationed there -- even though it's prone to sinkholes. In the winter, the parade ground was sometimes flooded to form a skating rink.2

Those officer's barracks are still in use, most of them serving as residences, while the one nearest the main road is now the Visitors Center. The cottonwood trees lining Officer's Row were planted with, shall we say, military precision: they form a perfectly straight line from one end to the other. That flat area between Capitol Hill and the yellow hotel and restaurant on the left was a parade ground for the cavalry troop stationed there -- even though it's prone to sinkholes. In the winter, the parade ground was sometimes flooded to form a skating rink.2The Army gave up command in 1918, when the newly-minted National Park Service was up and running. They were ready to go, since it no longer made sense to station soldiers along the former frontier when they were badly needed elsewhere. But they left behind some solidly-constructed buildings and a helluva lot more wildlife than there would have been without them.

More reading:

Bartlett, Richard A. A Wilderness Besieged

Haines, Aubrey L. The Yellowstone Story

_____________________________________________

1. There was already a hotel at the site, to serve tourists who wanted to explore the hot spring terraces before heading off into the interior.

2. This is still done today, but behind the hotel and not on the parade ground.

Labels:

history,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, May 13, 2011

Friday photo

One of the last photos I took in Yellowstone and one of my favorites (you'll probably need to click and enlarge it). I had just composed this scene of the sunset over the Yellowstone River -- the cheapest and easiest way to engage in nature photography, let's be honest here -- when three pelicans swooped in from the left. I saw them just in time to delay tripping the shutter* and waited until they entered the frame. Ah, and then one of them tired of the others' conversation or something, and decided to land in the river. What a stroke of fortune; the outstretched wings and the ripples from his feet breaking the water are just so much more dynamic than the river and sky, or even than the three birds in flight would have been.

Pelican flight is absolutely gorgeous and stately. They don't do aerobatics like the swallows that nest under the eaves of Lake Hotel. They don't flap frantically. They glide through the air as if on a tram, faster than hawks and eagles normally soar, more immune to buffeting breezes that bounce seagulls about. Once my sister and I were standing on the high bluff on the east side of LeHardy Rapids, looking down on the river, when a similar flight of three pelicans suddenly swooped into view below us. A video could never convey the effect; such serendipitous beauty can only be savored in the moment.

Which is to say, I hope you enjoy the photo. But it's not the same as being there.

____________________________________________________

* An unfortunate feature of digital cameras is that they take several seconds to save the digital file between each shot, unless you've set the camera to 'burst' mode. Landscapes don't usually move, even in a volcano like Yellowstone, so I didn't typically use burst mode.

Labels:

photography,

wildlife,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, April 22, 2011

Friday photo

It's peculiar that I had lived in Yellowstone for so many years before I ever caught Tower Fall at the right time of day for this scene: the massive spray from the waterfall backlit by strong sunlight, filling the entire canyon with a dazzling light. I have this scene in both slides and born-digital images and may have to scan one of the slides someday for comparison.

Tower Fall is a fine example of a hanging creek, a small river that's cutting downward as fast as it can, but just can't keep up with the more powerful and erosive river that it empties into. In this case, Tower Creek has to drop 132 feet in order to catch up with the mighty Yellowstone River just a couple hundred yards away. Multnomah Falls near Portland, Oregon, is an especially spectacular example, if you happen to be going that way.

The creek and waterfall were named by the members of the Washburn expedition of 1870 early in their explorations. In his account of the expedition, Nathanial Langford added this footnote to the story of the naming of Tower Fall:

At the outset of our journey we had agreed that we would not give to any object of interest which we might discover the name of any of our party nor of our friends. This rule was to be religiously observed. While in camp Sunday, August 28th, on the bank of this creek, it was suggested that we select a name for the creek and fall. Walter Trumbull suggested "Minaret Creek" and "Minaret Fall." Mr. Hauser suggested "Tower Creek" and "Tower Fall." After some discussion a vote was taken, and by a small majority the name "Minaret" was decided upon. During the following evening Mr. Hauser stated with great seriousness that we had violated our agreement made relative to naming objects for our friends. He said that the well known Southern family -- the Rhetts -- lived in St. Louis, and that they had a most charming and accomplished daughter named "Minnie." He said that this daughter was a sweetheart of Mr. Trumbull. Mr. Trumbull indignantly denied the truth of Hauser's statement, and Hauser as determinedly insisted that it was the truth, and the vote was therefore reconsidered, and by a substantial majority it was decided to substitute "Tower" for "Minaret." Later, and when it was too late to recall or reverse the action of our party, it was surmised that Hauser himself had a sweetheart in St. Louis, a Miss Tower. Some of our party, Walter Trumbull especially, always insisted that such was the case. The weight of testimony was so evenly balanced that I shall hesitate long before I believe either side of this part of the story.

Given Nathanial Langford's track record with campfire stories, I wouldn't hesitate an instant before disbelieving every side of this part of the story. His tale of the origin of the national park idea, that the party was camped at the confluence of the Firehole and Gibbon Rivers (to form the Madison) discussing the profits to be made from claiming the areas around the waterfalls and geysers under the Homestead Acts and charging tourists to see them, when one of his companions solemnly declared that they should reject such base scheming and work to have the area given over to the people as a national park -- well, that story has long been debunked, with a corresponding decline in Langford's reputation as a scrupulous man.

In any event, Walter Trumbull ended up marrying a woman named Slater, while Samuel Hauser married one Helen Farrar only a year after this supposed campfire spat. You'd have thought naming a waterfall in the first national park after your lover would earn you a few more boyfriend points than that, but women are fickle, I suppose. Neither man ever managed to marry a Miss Tower or Miss Rhett.

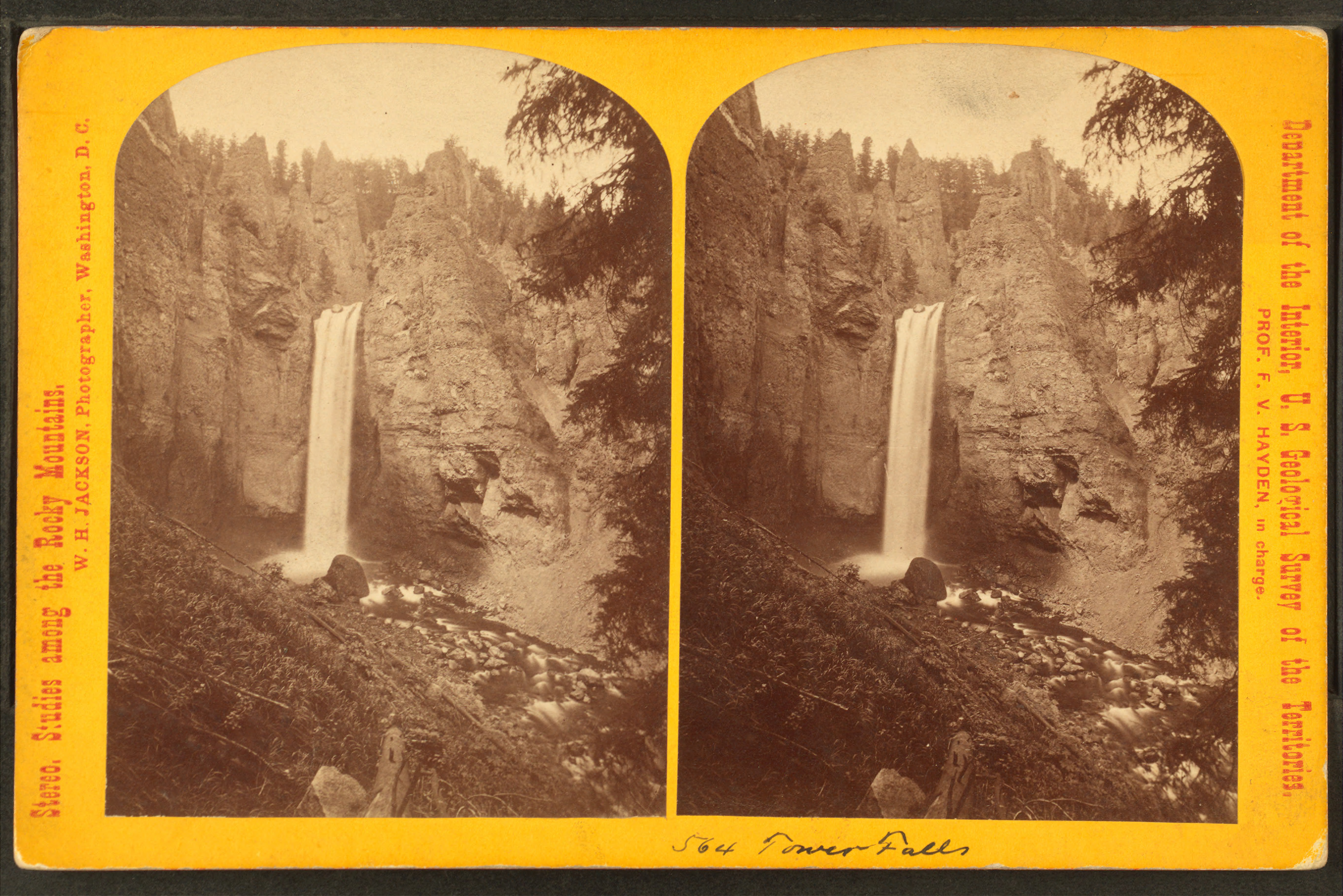

This William Henry Jackson photo nicely illustrates why "Minaret" would have been an entirely appropriate name for this waterfall. The sketch below was made by one of the soldiers on the Washburn expedition and, as far as us white folks go, is certainly the very earliest pictorial representation of Tower Fall.

This William Henry Jackson photo nicely illustrates why "Minaret" would have been an entirely appropriate name for this waterfall. The sketch below was made by one of the soldiers on the Washburn expedition and, as far as us white folks go, is certainly the very earliest pictorial representation of Tower Fall.

By the way, if you click on the Jackson photo and look closely, you'll spot a small boulder perched precariously on the edge of the waterfall. For over a hundred years, tourists enjoyed speculating on how long it could stay there; it looked like it should fall any minute, but maybe it would last another century, or two, or three? Well, it didn't. Spring floods knocked it off the edge in 1985 or 1986, shortly before I first laid eyes on Tower myself. Alas.

Labels:

history,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, April 8, 2011

Friday photo

Here's a photo of Topnotch Peak, one of the more identifiable peaks of the Absaroka Range that forms Yellowstone's eastern boundary. It's a fairly generic photograph, just a mountain top rising above the forest. It doesn't even give you a good view of the eponymous “notch.” In fact, I find the photograph so non-descript that I'm slightly surprised to have found it still amongst my 35-mm slides.

I recall a conversation in the Employee Dining Room at Lake once: one of my coworkers was explaining to someone how he had thrown away thousands of slides over the years. “Oh, you throw them away because you don't have room to keep them?”

“No, I throw them away because they suck!”

I've thrown away a lot of slides over the years, for both of those reason. Some were just too dreadful to ever pass muster with the editor (me). Others were not bad, but I didn't have room to save every slide I ever shot. I was traveling between Yellowstone every summer and wherever I was during the winter. I lived out of dorms for the entire 1990's, moving at least twice a year and having to pack all my belongings into a Ford Escort. You get good at packing; I recall having to empty the entire car to get at the spare tire on the side of a Nebraska highway one night, repacking to get back on the road, then repeating the process at the tire shop the next morning. One of the guys in the shop just shook his head in amazement: “I never thought that would all go back into that car.” Having my entire photo collection whittled down to three 3-ring binders was just one way of keeping the load manageable.

It means that there are some feature or places for which I have no photographic record at all, because whatever picture I took of the place didn't survive the editing process. If I didn't like it as a photograph, I didn't save it as a “record shot.”

Now that I don't need to save space, it's ironically so much easier to save space. I no longer throw away – i.e., delete – digital photographs, because I can easily archive everything onto a hard drive that's smaller than a desk phone. And those two bulky cases filled with 120 cassette tapes are gradually being replaced with MP3 downloads (the later collection of CD's having already been ripped to disc) and I can have as much music as I desire without worrying about where I'm going to fit it all.

The electronic gadgets sure makes the peripatetic life more comfortable. In fact, I read a blog entry a couple years ago about a young man who was experimenting with being homeless. He had a duffle bag with clothes and a few electronic devices that gave him all the music and reading material he needed, while still being able to carry everything he owned. He was also depending on a network of friends to provide him with couches to sleep on, so I don't expect he's made a permanent life out of it. But the idea that you could have such an array of cultural amenities without a permanent home to store it in still amazes me. How Young Me would have envied Old Me!

Labels:

technology,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, April 1, 2011

Friday photo

An indecisive leader. This cow was at the head of a small herd crossing the river and had picked out a spot on the opposite bank to climb out when -- how unexpected! There was this stupid photographer standing in her way. Not at all sure how dangerous he might be, she hesitated and the rest of the herd stopped behind her while she dithered.

I hadn't meant to be so obnoxious. I just saw the elk in the river and thought "cool picture." It wasn't until I had snapped a couple that I realized what was going on -- I was a strange animal standing in her path and the elk were being extra cautious about me.

It's a funny thing about elk, and bison and bears and moose as well. They get used to seeing people in certain places, especially along the roads. They'll scarcely notice. I remember reading a magazine article once where some young environmentalist claimed, "If you look at photographs of animals in Yellowstone, you can see the fear in their eyes from the crowds!" It's nonsense, of course. Even if you could accurately judge an elk's emotions from a 1/250 seconds glimpse of its face, the fact is that wildlife can become quite accustomed to humans.

I've often seen elk grazing right alongside the roads in some place like Gibbon Meadows, where they had a mile or more of unoccupied meadow to retreat into if the people bothered them. Or the herds that regularly descend on Mammoth Hot Springs and its manicured lawns, scarcely less human-infested than Old Faithful itself.

Speaking of Old Faithful, I recall one summer when an old bull bison decided he liked the shade between the Bear Pit lounge and the Inn's back door (a busy door, since the parking lot in the back is much bigger than the one in front of the Inn). It lasted about a week or two, with the rangers blocking off the sidewalk whenever the bull showed up; the crowds certainly didn't intimidate him in the least.

But as I said, that's in certain places. Hike just a little ways from Mammoth and that same herd of elk will not allow you near them; I've had elk stop and stare at me from half a mile away, and then turn and run over a hill. I'm about the size of one large wolf, if it stood upright, which seems to be enough to alarm an entire herd of 500-lb cows. Even a herd that wouldn't blink at an entire busload of 200-lb Americans unloading a few steps away, had they been down the hill in Mammoth. But they do get alarmed. Some places they expect people. In other places they don't, and in those cases they don't have the same expectations of harmlessness. It's almost as if they don't recognize that it's the same sort of animal in the woods as it was by the road.

The cow above had just come from the side of the river opposite the road. She was coming from the backcountry into the frontcountry and I don't think she was prepared to see people at all. So it triggered all the attentive caution that is natural to heavily-predated animals. "Wait! What's that in front of me? I don't know, but it's looking at me. This could be trouble; better stay put until I see what it's going to do...."

I didn't want to be an asshole, so I snapped the last photo and scurried back to my car. The elk finished their crossing in peace.

Labels:

wildlife,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, March 25, 2011

Friday photo

When I began Googling around for some quick info about the petrified trees on Specimen Ridge, I got a surprise: most of the hits that came up were from creationist websites. Yes, believe it or not, the young-earth creationists get all in a tizzy about Yellowstone's ancient forests. They're worth getting excited about, no doubt about that, because like most things fossilized, they give you a rare glimpse at a long, long vanished world.

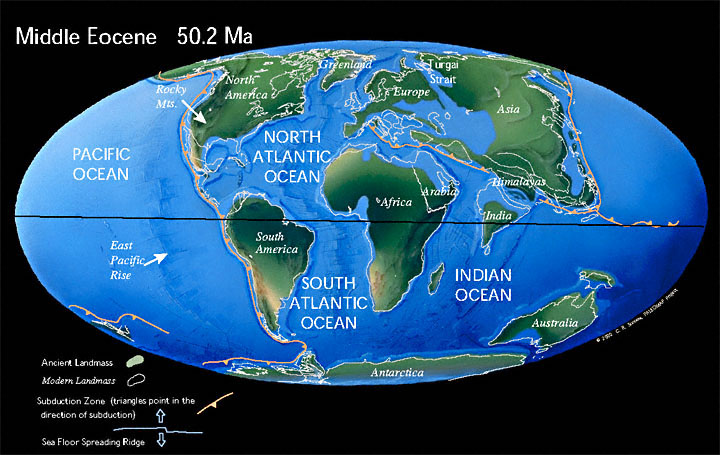

The geologists who have examined the slopes of Specimen Ridge have identified at least 27 successive layers of forests, each destroyed and partially buried under volcanic ash from Mt. Washburn, then an active volcano. The estimate is that these layers represent some 20,000 years of growth/catastrophe/regrowth/catastrophe/regrowth, beginning some 50 million years ago.

If that seems like a long time ago, just remember that the Earth had already completed 99% of its current history by then. The dinosaurs were only recently deceased, the supercontinent of Pangaea had broken up, and the continents of the western hemisphere looked pretty much as they do now:

(Image via the Paleomap Project)

(Image via the Paleomap Project)Still, from our vantage point, a long-vanished world. The trees found in these buried forests have living relatives and, if their current environments are any indication, Yellowstone in those days was a warm, humid place comparable to present-day Georgia. There are plenty of redwoods in these forests, but also maple, sycamore, walnut, chestnut, oak, dogwood - even magnolia trees. It doesn't take too close a look at my photo to realize that nothing like these will grow there today. Judging from the fact that all of the fossilized roots (when they can be found) show horizontal development, none of these trees seems to have grown on a hillside; each forest occupied a fairly flat valley and was buried under another level accumulation of ash and mud, until the earliest layer was some 1200 feet deep. The silica in the ash was absorbed into the wood, causing the fossilization that has preserved the trees to this day.

That all of this should provide fodder for creationists comes as rather a surprise, but it seems to all trace to a single geologist named Harold Coffin (Ph.D. from USC in 1969). He appears to have been associated with the creationist Earth History Research Center at Southwestern Adventist University (where they have a single Department of Biology and Geology!), but isn't listed as a current faculty member, so I'm not sure where he is nowadays. But Coffin has published on Specimen Ridge, claiming that the trees must have been transported to their present location; he has also reported finding upright floating stumps in Spirit Lake at Mt. St. Helens, which he suggests would explain the standing trees in Yellowstone.

Not everyone agrees that the trees have been transported; in fact, I don't find that anyone else believes that Yellowstone's fossil trees came from anywhere but Yellowstone, allowing for some movement due to rapid lahars. But Coffin's work is all over the creationist websites, the same claims over and over again. Upright logs in Spirit Lake! Therefore the Flood! QED! It takes so little to make a creationist happy, particularly when you're talking about evidence.

But that's the general approach that creationists rely upon: pick out one little line of evidence, try to poke a hole in it, and then imagine that all of geology, paleontology, and biology would collapse along with it. Why petrified trees being carried to Yellowstone by flood waters or mud flows would prove a young earth is hard to fathom, but they're sure it's so.

If you really want to look at the trees in my photo and imagine that they floated there in a magic flood and came to rest in an upright position, go ahead; I can't stop you. I'll wait until some geologists who aren't under the influence tell me that it's so and, until then, use my imagination to picture beautiful hardwood forests filled with strange-looking animals (Uintatheriums, for example) walking across land that's going to get buried under volcanic ash, then get eroded away again until, 50 million years later, I can hike up a ridge and sit next to three of those very same trees. That's grander than any creation story I've ever heard.

________________________________________________

Main sources:

Erling Dorf, Petrified Forests of Yellowstone. National Park Service, 1980.

William J. Fritz, Roadside Geology of the Yellowstone Country. Mountain Press, 1985.

Labels:

geology,

religion,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, March 18, 2011

Friday photo

The beautiful Yellowstone River moves gently down from its slow, meandering sojourn through the Hayden Valley. All is calm as night falls, and has been ever since leaving Yellowstone Lake some twelve or thirteen miles ago. Oh, a few small rapids here and there, but otherwise as placid as you could ever hope for a mountain river to be.

What awaits it in just a couple of miles is something entirely different: two large waterfalls and a deep, narrow canyon that will change its character from gentle serenity to murderous, frothing fury in just a few hundred yards. The first fall is 109 feet; the second is 308*. During the spring runoff, that can be some 50,000 gallons of water racing over the edge every second. And if you can't imagine what it's like to be a river pulled off the edge of a cliff, you can park your car and walk down to the brink of either one of these falls and get a strong sense of its power - deafening and vertigo-inducing.

There's another significant waterfall before the river leaves park, Knowles Fall in the Black Canyon, a mere 15-footer that still manages to impress. More rapids and canyons. But no dams, none at all until after it has joined the Missouri and surrendered its name. The Yellowstone has the eminent distinction of being the longest free-flowing river remaining in the lower 48 states today, at almost 700 miles without a dam. It arises just outside the southeast boundary of the Park, in the Thorofare Region that is reputed to be the most remote place in America, outside Alaska -- you could find yourself as much as thirty miles from any excuse for a road. And between its headwaters and the falls, it becomes Yellowstone Lake, the largest freshwater lake in North America at greater than 7000 feet of elevation. It is indeed a river of superlatives.

This is the river that gave Yellowstone National Park its name. My one and only contribution to Wikipedia was to correct the mistaken notion that the park was named for the color of the rocks in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (just below the aforementioned falls). Not so. The river was already known to American fur trappers as the Yellowstone when Lewis and Clark came through in 1804-05, a name the English had translated from the French, which the French had probably picked up from the Minnetaree.

Who knows how far back the name goes? A good bet is that the Indians named the river for the yellowish rock you can find downstream in the general vicinity of modern-day Billings. And so, even without much knowledge of the Canyon area and its impressive colors, it was natural that the Park would carry the river's name. In the late 1860's people knew only two things about the region: some mountain men's very tall tales came out of that area, and so did the Yellowstone River.

____________________________________

* The Lower Falls is commonly described as "twice the height of Niagara," but it's really about 25 feet short of the mark it would need to make that accurate. But close enough that you should be suitably impressed.

Labels:

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, February 18, 2011

Friday photo

Last Saturday I finally got out to do a little bit of skiing and decided to check out the Hudson Mills Metropark, a 1500 acre spot of woodlands northeast of Ann Arbor. It's a good thing I did, since the snow began melting that morning and, with several days near 50°, the snow has turned to puddles. In fact, I think we're halfway to flood stage around here.

The park doesn't have much in the way of hills, so the skiing was just a bunch of looping round a 5-mile trail system, with an occasional bit of glide. But there were a lot of novices out and it was fun to watch them approach these tiny little slopes, with their terrifying 5% grades. Knees locked, thighs stiffened, weight thrown forward, skis locked into wedge positions, pushing tentatively on the poles, probing for that point at which gravity will take over and speed them into reckless disaster. It was so cute.

I say that with compassion, because to this day I am not a strong skiier and I vividly remember how helpless you feel when you first bind boards to boots. Sure, you don't get going all that fast on a small slope, but since you have no control yet, anything is too fast. As soon as you begin to glide downhill, you're a passenger. I would regale coworkers with my latest crash: I didn't get my arms and legs fully extended, so I guess it wasn't a proper cartwheel ....

What astonished me after that first winter was to go back after the snow was gone and to realize how gentle many of those slopes were. Not that they weren't racy - there are some good speedy hills around the Old Faithful area. But they still didn't look as steep as they felt. Surely that slope at the bottom of the Fern Cascades trail was 45°, wasn't it? It was so fast! But it's probably closer to a 10°-15° slope.

I spent that summer examining all the hills I encountered with a sort of slideshow in my mind, one that would replace the grass with snow and imagine that I was about to hurtle down on my second-hand Rossignols. It's a funny thing, but the world's terrain just doesn't look as rugged as it feels. Which is why cartographers who want to portray relief often have to exaggerate the vertical scale relative to the horizontal; everything looks too flat otherwise, even in the mountains.

Here's an example by the cartographic artist Heinrich Berann, who did a series of panoramas for the National Park Service. He produced his view of Yellowstone in 1989:

That's a hell of a lot of vertical exaggeration, especially of the Tetons in the distance. But it gives you a more intuitive sense of the shape of the land than a truer representation would. Much like people may be more readily recognized from a caricature than from a photograph, I suppose.

That's a hell of a lot of vertical exaggeration, especially of the Tetons in the distance. But it gives you a more intuitive sense of the shape of the land than a truer representation would. Much like people may be more readily recognized from a caricature than from a photograph, I suppose.

Labels:

cartography,

sports,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, February 11, 2011

Friday photo

It's been a cold winter in Michigan this year, with heavy snowfalls to boot. Here in the southeast corner, we didn't get hit as hard with the last storm as, say, Chicago, because the heaviest snow passed to the north of us. But the last several evening have seen temperatures drop below zero Fahrenheit and bundling up is a useful skill.

I still benefit from my winters in Yellowstone. On cold days like we've had lately, I add a layer of thermal pants and shirt, two layers of socks, and a heavy sweater. With that, I only need add the windproof jacket and I'm plenty comfortable at the bus stop. It means I'm a little overdressed for indoor work, but I've always found that easier than being too cold. And I get the smug pleasure of enjoying weather that even hardened Michiganders gripe about. I still own a heavy coat that I bought for my first winter at Old Faithful, and which I wore perhaps two dozen times in while I was there and not once since leaving the Park.

The photo above? Taken at sunrise while temperatures were still fifteen or ten below zero. The sun isn't quite high enough to illuminate that layer of low-hanging fog, which seems to divide the world into a dark side and bright side.

Labels:

photography,

wildlife,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, January 21, 2011

Friday photo: hot water, cold air

Last Monday it was so warm that it rained, but now it's turned cold again and we're not expected to reach 20° over the weekend. So here's some cold weather fun.

Geysers are at their best on a cold winter's day, when the hot water turns into volleys of little ice rockets, each at the end of its personal vapor trail, as you see above. It's a simple matter of surface area:mass ratio -- lots of little drops will freeze or evaporate faster than one large body of water because more surface is exposed to the air. It happens so fast that most of the water evaporates and the remainder freezes before it can ever hit the ground.

I don't understand why hot water evaporates quicker in cold air than warm air. You'd think it would be easy to discover, what with this awesome new intertubes thingy, but no. I haven't found anyone who explains it directly. So here's my best guess: since transitioning between water and vapor requires energy, evaporation happens easier when more energy is transferring between the water and the air, which happens faster when there's a greater difference between water and air temperature. So T(water) - T(air) = k*Evaporation rate.

That might be totally wrong. Maybe it's all about the humidity. We all know that cold air is drier than warm air, so maybe that's the major reason why the geyser basins so fill up with steam on colder days - because the air is drier, not because it's colder. That's certainly a factor, but I'd be surprised if it's a large one.

I posted this photo is a response to this great video which is getting a lot of attention this week. Yellowknife is only 4° south of the Arctic Circle and they expect a high of -27° F. today, which is quite a bit colder than it was the day I took my photo above. The evaporation is wickedly dramatic:

Not even a hat or gloves. Now that's a Canadian.

Video via Daily Dish

Labels:

nature,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, January 14, 2011

Friday photo

Relaxation made flesh. Once you've packed on the extra hundreds of pounds and are just waiting around for winter, that's how it goes.

It was a few years earlier, at this same site, that I thought I might get killed by a bison. Nothing came of it, but for a minute I thought I was in considerable danger. I had shot a couple photos of bison, just like this one, then saw the sun going down behind the creek, so I moved up onto the bridge to take a few shots of the creek. When I finished, I turned around and found that a number of cars had stopped to look at the bison, spooked them a little, and they were all fleeing the pack of cars -- right across the bridge. The one I was standing on.

Normally, a bison has a very sedate, deliberate walk. He'll cover a surprising amount of ground in a short time, but he won't look like he's in a hurry. When a herd starts trotting and huffing and grunting, it means they're a little agitated. That's what these guys were doing and half the herd was passing right by me, blocking both ends of the bridge.

I had the option of jumping over the side and down to the creek, but it was a fifteen foot drop and the creek is too shallow to break a fall. I mean, the bottom of the creek would break your fall, not the water, which means it would hurt more. Besides, the hitherto-unaccounted-for other half of the herd was crossing the creek right below me. It looked bad.

So I turned, sat on the abutment, and waited. One particularly large fellow seemed to be headed straight for me and I braced myself for impact. Then he swerved and just hustled on by. The rest did the same.

I've seen bison tolerate an entire busload of tourists lining up five feet away for a photo; at other times, I've seen them charge people from over a hundred feet away. It's not always clear what triggers a response. Here's a video of a bison chasing tourists at Old Faithful, for unclear reasons. When the bison lies down to wallow at the end, the narrator says, "Now he's taking a nap." Not really; wallowing is what a bison does to deal with the discomfort of skin parasites and maybe this animal was already in a bad mood because of the itching.

Here is what a bison usually does: just charge the annoying people and, when they run, settle for having made his point; without language, he still manages to say "Get out of here" in unmistakable terms. Here's what happens, though, when they carry through with the attack. You don't want that to happen to you.

Labels:

wildlife,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, December 17, 2010

Friday photo

Whee! Winter has arrived in southeast Michigan, snowy and cold as God intended it. Now if we can only get still more snow, and maybe have steam rising out of the ground to coat the trees with ice, it would look as wintry as Yellowstone.

Labels:

photography,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, December 10, 2010

Friday photo

Doublet Pool is one of the most attractive thermal features in the Upper Geyser Basin, if you find it - it's tucked away on Geyser Hill, across the Firehole River from the lodges, stores, and benches for viewing Old Faithful. I don't mean that it's really hidden away, but just that the folks who don't bother walking through the basin won't get to see it.

Doublet has been known to erupt slightly with a bit of bubbling, and on rare occasion even throw some water a couple feet in the air. Usually, though, it's just another of the steaming hot pools, with that clear blue (bacteria-free) water that the hottest pools have, and the red bacteria mats in the shallow areas where the water is merely warm and can sustain thermophilic life. It's called Doublet because there are two small pools connected by the narrow channel that you see in the photograph.

I don't entirely understand how the scalloped edges form. Silica is precipitating out of the water, slowly building up the mass on the sides of the pool. But why the round scallops? There's no sign of water draining into the pool and cutting channels; those would look like gullies instead of scallops, anyway. My best guess is that the edges begin jagged and random, but as the silica accumulates, it does so at equal distances around any pointed surface (recall that a circle is defined as the set of points equidistant from a given point). The tendency would be to grow the rounded scallops out from the edges of the wall and ever farther into the pool; pointy edges can't help being a passing phase. Or maybe there's some entirely different reason for that shape.

Labels:

photography,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, December 3, 2010

Friday photo

Two weeks ago I posted a photo of the Old Faithful Inn, whose railings and faux supports are made of bare lodgepole pine logs. These were originally put in place with their bark intact, but the logs were "peeled" in 1940. Lo and behold, it was discovered that Nature had already decorated the beams with an intricate grooved tracery, courtesy of countless pine bark beetles. No one knew.

Similarly, the tree above has been scoured by beetles, whose action would have been invisible until the tree was killed during the 1988 North Fork fire. I have to admit, I don't understand why the outlines of the beetle trails are darkened, but not the interior or the rest of the tree. But it's an attractive arrangement nonetheless. Nature is an artist.

I doubt the patterns have as much mathematical structure as has been claimed for Jackson Pollock paintings (purportedly an intuitive application of fractal patterning), but that section to the left looks to me almost like a form of writing, perhaps the sort of thing that Mayan glyphs might have evolved into over time.

By the way, leaning into a tree while standing on a 30-degree slope on skis is not the easiest way to get a sharp photograph. So I'm a bit proud of that.

Labels:

art,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, November 19, 2010

Friday photo

In 2004, Yellowstone celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Old Faithful Inn, an originally quaint, now Byzantine wooden hotel that sits exactly one eighth of a mile from Old Faithful Geyser. Begun in the summer of 1903, construction was finished in time for the Inn to open the following season and it has been one of the most famous buildings in the West ever since.

That precise distance from Old Faithful Geyser is no accident. It was as close to the geyser as they could legally build. However, one notable, if often overlooked, feature of the Inn is that it is aligned to direct visitors' attention away from the geyser and toward the rest of the geyser basin. If you stand outside the front door, or lounge on the observation deck above the porte-cochere, you have to make a 90 degree turn to the right in order to look at the geyser. Looking straight out presents you instead with an invitation to discover the rest of the amazing Upper Geyser Basin, full of wonders such as Castle Geyser, Grand Geyser, Morning Glory Pool, and -- not the best, but my favorite name -- Spasmodic Geyser. If you come to the Inn and don't discover there's more to Old Faithful than Old Faithful Geyser, it's your own danged fault.

Unfortunately, the two huge wings added to either side in 1913 and 1928 spoiled the balanced appearance that the Inn originally presented (as well as blocking the view of Old Faithful from the dining room). Besides sprawling like overturned tractor-trailers off both ends of the "Old House," they abandoned the log construction of the original, as well as the A-frame roofs.*

However, the interior is still a delight. What I like in this photo is the number of distinctive Inn features I was able to gather into a single image. The distinctive wooden supports, both in full view on the opposite side, and close up so as to show the beetle scorings that create the most incredibly artistic-yet-natural effect; the US flag hanging over the lobby; the old electric lights; and, for the anniversary season, the large banner suspended from the ceiling and one of the smaller banners hung from the balcony. I rather regret the speaker in the lower right corner, as well as the light coming in from the dining room, but otherwise I enjoy the harmonious composition. This is one of those photographs where I spent a good twenty minutes fussing because the tripod was six inches too far to the left, or had raised the camera four inches too high.

The immense open space in the Inn lobby has been known to scare the hell out of modern structural engineers who venture into the building. The supports in the upper reaches look, shall we say, spindly, and they all seem to run mainly lengthwise, implying that the seven-story roof has no cross support. Apparently, that support exists elsewhere and the building is safer than it looks, and considering that it has stood for over a hundred years in a seismically-active region, and, survived the 7.4 Hebgen Earthquake, it would have to be.** Nonetheless, the recent renovation project has addressed some of the structural concerns, as well as making many aesthetic alterations. I left Yellowstone just as they were beginning and haven't been back in the meantime, but you can learn about them here.

Further reading:

Quinn, Ruth. Weaver of Dreams: The Life and Architecture of Robert C. Reamer.

Reinhart, Karen Wildung, and Jeff Henry. Old Faithful Inn: Crown Jewel of National Park Lodges.

_________________________________

* The flatter roofs are much friendlier to the winterkeeper who has to go up remove the snow that the high-pitch roof is supposed to shed, but doesn't always. In the film version of The Shining, we're told that a winterkeeper has nothing to do but putter around and keep the heat running; the truth is, there can be some hard work involved.

**I have heard it claimed, albeit not directly from an expert, that this was mainly because of the luck that the ground wave was traveling from northwest to southeast; had it come from another direction, the Inn would probably have collapsed.

Labels:

photography,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, November 12, 2010

Friday photo

I'll give you a second to figure out what's going on with this photograph. I did introduce a little digital noise, to give it a grainy look, and removed the color. But all that fuzziness and squiggly contours in the trees are entirely natural - no filters, no Photoshop work.

The trick is to realize that the photo is upside down. This is a reflection in the lake, a lake that was quite calm but supplied just enough ripples to distort the image of the shoreline. I just love the effect, especially the blurred distant forest on the left side.

Labels:

photography,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, October 29, 2010

Friday photo

Colter Bay is, of course, named for the famous mountain man John Colter, who is suspected to be the first white man to visit Yellowstone. We're not sure -- it seems pretty certain that he traveled through Yellowstone, but there's every chance that some French or Spanish explorer might have been there shortly before him, without leaving a record.

Colter was on his way back to St. Louis with Lewis and Clark when he met up with a pair of trappers; with his commanders' permission, he left the expedition and went with his new partners. That venture didn't work out, but he met up with Manuel Lisa of the Missouri Fur Company and decided to try the trading business again. It was while employed by Lisa that Colter made his journey through the northern Rockies, locating native bands and trying to persuade them to conduct business with the Missouri Co. This was in the fall and winter of 1807-08.

A few years after this trek, Colter met up with William Clark again and the two discussed his travels. Almost all we know of Colter's route is all based on this notation in the map Clark was compiling of the West:

Remember that Clark and Lewis had taken careful observations of the route of the Missouri River; it's very accurate on the map, as are the locations of its major tributaries. Lisa's fort was at the mouth of the Bighorn River, near present-day Hardin, Montana, and Colter seems to have ascended the Bighorn, turned west at the Shoshone River, and probably reached present-day Cody. Clark's map indicated "Boiling Springs" there, and although the hot springs around Cody are no longer active, there are other contemporary accounts of them; in all probability, this was the site referred to as "Colter's Hell," a name that was later - and erroneously - applied to Yellowstone itself.

That much is pretty clear from Clark's map, but after that it gets murky. Clark was filling in areas based on verbal reports, without the benefit of systematic surveys, and the results are rather imprecise, to say the least. But his map does contain two lakes, which he named "Eustis" and "Biddle." And it just happens that this area, in reality, contains two of the most prominent lakes in the Northern Rockies: Lake Yellowstone and Jackson Lake. Anchoring a reconstruction around these two landmarks, it's possible to make a plausible guess where Colter went.*

It's been proposed that he crossed over Togwootee Pass into Jackson Hole, but the map shows him skirting well south of Jackson Lake; therefore, it seems more likely that he made the difficult passage over the Wind River Range via Union Pass, between present-day Dubois and Pinedale. If that's the case, then he probably followed the Hoback River up into the south end of Jackson Hole.

It's pretty well accepted that he crossed the Tetons, probably at Teton Pass between Wilson, WY, and Victor, ID, and went north through the flat valley west of the Teton Range. The approach to "Lake Biddle" from the northwest would suggest that he crossed the northern end of the Tetons and encountered Jackson Lake for the first time.

From there, he apparently went north and found Yellowstone Lake, although it seems odd that the Snake River should be shown so truncated - it would have been the logical route all the way up to Lewis Lake or beyond. Then along the western shore of Yellowstone Lake and up the Yellowstone River - except now there are a couple more problems. The major discrepancy is that the outlet to the lake is shown to the southeast, almost 180 degrees opposite of reality. It's hard to account for an error that large, since nothing about the geography would suggest that Yellowstone Lake drains from anywhere but its northern end. Perhaps Clark simply misunderstood what he was being told.

Second, it seems surprising that Colter traveled along the west side of Yellowstone Lake without noticing the West Thumb thermal area. It would also be weird if he saw them, but didn't find them as worthy of mention as the "Boiling Springs" near Cody. Of the two possibilities, the former seems more explicable to me.

For the rest of the route, Colter is presumed to have reached Soda Butte Creek via the Lamar River, and thence to Clark's Fork and back to the Yellowstone, perhaps near Laurel. Again, it's awfully hard to make sense of Clark's map on this point. He shows Colter descending the left bank of the Yellowstone, then crossing it and, instead of following a tributary (as the Lamar is), crossing a divide into a parallel river basin. But there's really no better way of getting from Yellowstone Lake to Pryor's Fork than that, and it's pretty solid that he did travel between those two places.

If this reconstruction is accurate, this would be the approximate route that Colter took:

View Colter's route? in a larger map

_________________________________

*My description is largely based on the description in Mattes, Merrill J. "Behind the Legend of Colter's Hell: The Early Exploration of Yellowstone National Park," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Sep., 1949), p. 254.

Labels:

history,

photography,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()