A couple years ago I wrote a post about Charles Freeman's book The Closing of the Western Mind, which argues, in a nutshell, that the triumph of Christianity in late Antiquity truly did usher in an intellectual Dark Age, wherein philosophical and scientific questions (and there was not yet a distinction between the two) were settled by theological arguments from authority and free inquiry was discouraged. In A.D. 381, Freeman continues his argument, exploring in more detail how the late Roman emperors injected themselves and the state into theological disputes.

Several reviewer of the book have complained that Freeman in simply updating Edward Gibbon and blaming Christianity for the fall of Rome. This is not how I read Freeman. He blames Christianity – or, to be more precise, certain later Christians and Roman emperors, and the precedent they established – for killing off a great and ancient Greek tradition of free inquiry. But he does not blame Christianity for bringing down the Empire itself.

By the end of the 4th century, while Christianity was growing but did not yet dominate, the Empire was barely maintaining itself. Grown too large for its own governance, it had split into two coeval sections, with capitals at both Rome and Constantinople governing the West and East. The powerful Persian Empire threatened the East, numerous Germanic tribes were invading from the North, and Roman armies were spread across borders that had grown too long and too distant to be efficiently defended. With the military removed so far from the core of the empire, the interior trade routes were less well-guarded and commerce became more difficult and expensive.

Although the East retained a cohesive state for another thousand years, the West disintegrated both politically and economically. After 400, trade all but disappeared in Western Europe. Cities became small towns; the money economy disappeared; well-manufactured goods, once common in even a peasant household, disappear from the archaeological record. Rome's famous aqueducts went dry for a millennium, and even the lead and copper pollution levels recorded in ice cores testify today to the demise of manufacturing during the Medieval Period.

***

None of this does Freeman blame on Christianity. Given the entirely worldly difficulties that Rome faced, it should be no surprise if the Empire failed to overcome them all. As I read Freeman, he would instead blame the fall of Rome for the intellectually authoritarian turn that Christianity took following the 4th Century. Throughout the Roman world, the scholarly decline was almost comparable to the economic and political collapse. According to Freeman's account, even the renowned Medieval scholars are recognized to have written poorly and less grammatically than their predecessors; where a rich Roman citizen could possess a library with thousands of works, medieval monasteries would be considered impressive if they contained a few hundred. Theology replaced naturalistic inquiry. A Christian mob probably destroyed the remnants of the Great Library at Alexandria1 in 391, and in AD 529, Plato's Academy was shut down after 900 years of free inquiry. Had the Christian authorities not been so hostile to non-Christian literature, more would likely have survived to the present day.

What happened? By Freeman's reckoning, the emperors meddled in theology and set a precedent of resolving scholarly disputes through authority instead of inquiry. As the Empire's organization became ever less adequate to meet external threats, the later emperors were prone to blaming their ineffectiveness on a lack of internal unity. And as Christianity absorbed more and more of the Empire's inhabitants, the emperors began to see the divisiveness of the Church as a principle weakness of the empire. In the centuries after Jesus's death, Christian clergy had taken the Greek practice of philosophical disputation, applied it to theology, and then – disastrously – made it a matter of eternal life or death to declare and defend a single position. “I don't know” was not an acceptable answer, even though it would have been the best answer to questions which were essentially unknowable.

One of the major, unknowable, questions concerned the exact nature of Christ – was he fully human, or fully divine? Maybe he was a human who was temporarily occupied by God? Or was he entirely God all along and only appeared human? However you answer the question, some unpleasant consequences seem to follow. If he was human, then why should we be worshiping him? Or if he wasn't human, then he could hardly have suffered through his crucifixion, in which case his great sacrifice would seem to be greatly overtouted. According to the disputants, immortal souls were at stake, although a cynic might notice that the emperors' habit of extending patronage to certain churches meant there was a lot of money and status at stake in elevating one's own views and disparaging a rival's.

The emperors began to take sides in these disputes, something that had never happened with philosophy or pagan religion. In AD 381, the emperor Theodosius issued an edict declaring the Nicene faith – an incoherent declaration that Jesus was simultaneously fully God and fully human, and you could conveniently flip from one to another whenever you needed to dodge a contradiction2 – was orthodox and that all other views were heretical. Clergy with contrary views were disfranchised and their churches closed. A decade later, Theodosius banned pagan rituals and sacrifices altogether.

Theodosius's efforts did not succeed in solving theological questions; all he managed to do was thoroughly politicize these disputes and cement the role of the state in establishing religious orthodoxy. Through the following century, Christians continued to gain strength and began to suppress pagan practices even more thoroughly than had been Christianity in earlier eras.3 Curiously, the disputatious eastern empire survived as the Byzantine Empire until 1453; it was the western empire, where theological questions seemed less urgent and there was no such thing yet as “papal authority,” that thoroughly fell apart.

As for the promises of orthodoxy … Freeman tells this story. In AD 428 the bishop of Constantinople, Nestorius, put the case as baldly and boldly as could be: “Give me, king, the earth purged of heretics, and I will give you heaven in return. Aid me in destroying heretics and I will assist you in vanquishing the Persians.” A few years later, Nestorius himelf was condemned for portraying Jesus as too human. Not that he had adopted any known heresy; he just wasn't orthodox enough. Thus the promise of fundamentalism; thus the all-too-often-delivered reality.

________________________________

1. The case is ambiguous and disputed. It seems likely that the Library suffered several episodes of destruction after its zenith in the last couple centuries BC. It's not clear how much was left to be destroyed by the mob in 391, but they did destroy what they found.

2. Yes, that's my own definition.

3. It comes as a surprise today to be told that the Romans were religiously tolerant, but it's fairly true to say they were. In conquered territories, they did their best to amalgamate local religion with their own, while polytheism would naturally tolerate anyone's decision to choose a certain god as his particular patron. An upstanding citizen would be expected to make a show of honoring a city's gods, just to keep them happy, but this didn't require him to reject any other gods. Jews refused to adopt polytheism, but they were never upstanding citizens (generally not legal citizens at all). I'm not well-studied enough to say this with confidence, but I suspect Christians would never have suffered persecution if the religion had remained confined to the lower classes; their religious views wouldn't have mattered to anyone.

Saturday, August 27, 2011

Book review: AD 381

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

Book review: American Insurgents, American Patriots

Ah, the American Revolution. The King was a tyrant so the colonists rebelled - it's as simple as that, isn't it? If you're not sure, just see what Schoolhouse Rock had to say about it. It's not too different from what my 6th grade teacher taught me.

Ah, but then you make the mistake of going to college, taking a history class or two, and it all gets more complicated. The taxes weren't that high, the colonists seem to have never felt prouder of the British Empire than they did in the 1760's, and the complaints mostly came from a handful of merchants in just one city. How did that turn into a wholesale revolution?

John Adams famously commented, "But what do we mean by the American Revolution? Do we mean the American war? The Revolution was effected before the war commenced. The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people."  TH Breen's latest book, American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People, addresses both how and when that happened.

TH Breen's latest book, American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People, addresses both how and when that happened.

In Breen's view, the revolution is not a steadily-rising tide of resistance as it's usually portrayed, from the Stamp Act crisis, through the Tea Party, and culminating in the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Instead, there was a particular revolutionary moment, and it occurred in 1774 when the British government reacted to the Boston Tea Party by imposing the Coercive Acts, designed to harshly punish the entire city of Boston.

The Coercive Acts were indeed dramatic. First, they reorganized the governor's Council and filling it with royal appointees, where before the democratically-elected Assembly had the councilors. Parliament judged that there was too much democracy in Boston and they intended to correct the imbalance.

More punitive yet, they closed Boston Harbor to all commercial traffic until the East India Company was compensated for the vandalism. This not only attacked merchants like John Hancock, but guaranteed economic distress among the poorer classes who worked on the wharves. Everyone would suffer until everyone had submitted.

And to enforce it all, the navy arrived to blockade the harbor, unloaded three thousand British troops in the city, and replaced the governor with a military commander. After eight years of negotiation and appeasement, Parliament had decided that the time for patience was over, and this time they would teach the colonists a hard lesson in obedience. The decision was disastrous.

The British believed that the loyal populace - surely the majority of the colonists? - would take courage from the invigorated royal presence and turn against that handful of noisy agitators who had gotten then all into such trouble. Wrong, utterly wrong. In the modern parlance, the battle for hearts and minds was over and the British had just lost, decisively and irrevocably. To the waverers who might have thought cries of Tyranny! were overblown, there was no longer any doubt. No, it was all true: Parliament had sent an army to wage war on Americans and intended to grind them into poverty and deny them the self-government they were accustomed to. Fear and anger overwhelmed the common folks outside Boston, who had until now been more spectators to the crisis. Almost overnight they became revolutionaries - or, Breen now calls them, insurgents. The moderates were suddenly radicalized.

The fear spread to the other colonies at the beginning of September that same year of 1774, when a strange event happened. Rumors began to fly around Massachusetts and Connecticut that the British navy had bombarded Boston, then landed and burned the entire city. They hadn't, but thousands of farmers and townsmen in New England grabbed up whatever guns they had and began marching toward Boston to exact revenge, before learning the truth and turning back.

The first consequence was that mob of farmers and townspeople - the folks who would come to style themselves Minutemen - had proven to themselves that they would really turn out in the event of war. Until then, they had been full of talk, but who knew how many of these braggarts would actually risk their lives if the British army began shooting? Now they knew: perhaps more than 20,000 had grabbed their guns and begun to march, easily enough to overwhelm Gage and his men. No matter that they had responded to a false alarm - they had responded, when the danger seemed extreme. Their pride, confidence, and radicalism soared.

But it also just happened that a first Continental Congress was gathering in Philadelphia right when the hysteria broke, and this had a strong effect in rallying the other colonies to Massachusetts's side. In the aftermath of the horror they had felt at believing the British army was killing people in Boston, the delegates voted to support the Suffolk Resolves, an appeal from a rather ordinary town in Massachusetts that called for the colonists to stop cooperating with the British government and to boycott all commerce with Great Britain. The members of this Congress were still rattled, but they also saw how inflamed the rest of the public was. In fact, the "leaders" of the resistance were now scrambling to stay in front of the mob.

At this point, a local resistance movement an intercolonial rebellion. The Continental Congress called for the total boycott and recommended that all communities set up a committee to enforce it. Breen loves these committees, because they made the Revolution a creative event and not just a destructive one. The rebels could retain their attachment to law and order, even as they removed the existing governmental structure by chasing away royal officials, and they could restrain mob violence and retain a fig leaf of due process, even as they enforced the revolution upon the unenthusiastic.

That due process was a bare cover for coercion, to be sure. The rebels tolerated no dissenting opinions or evasion of the boycott. Violators were likely to be called before the committee, or even visited by a mob of angry neighbors, and strongly urged to confess their error and recant. If they didn't, they could find themselves shunned by the rest of their community, perhaps wearing tar and feathers, or even having their house pulled down. Freedom of speech was not one of the revolutionary virtues in 1774. But two points bear emphasizing here.

One, these were neighbors, and violence was fairly uncommon, especially compared with other insurgencies and revolutions we know about. The patriots wanted reconciliation, harmony, and they wanted to control the message. All you had to do was go along: a full confession and apology would usually restore one to good graces. It was mainly outsiders (Scottish Presbyterian merchants, for example), former royal officials, or the most stubborn loyalists who received the rough treatment.

Second, I used the language of a religious inquisition. Breen doesn't use that terminology himself, but I don't think he would disagree with it, either. Many of the common people did understand their revolution in religious terms. Without reading Locke (and here I am returning to Breen's arguments), they believed their rights came from God himself. As a corollary, any government that would trample its citizens' rights had ceased to be godly and resisting tyranny was virtually a religious obligation. Just like religious authorities, the rebels wanted unanimity, or at least the public illusion of unanimity. And they had great success. The British hoped a majority of loyalists would stand up for the Empire; the rebels were out to prevent it and, whether or not they were more numerous (we don't really know), they were far more energetic than their opponents. For all practical purposes, the entire countryside really was on the side of the rebellion.

Despite their reliance on intimidation, the occasional use of tar and feathers, and even beatings and vandalism, the insurgents of 1774 managed to minimize mob violence, keep order, and maintain a functioning quasi-government in the midst of revolution. This is what Breen admires about the common people of the Revolution. He sees what so often happens in revolutions: unrestrained violence, endless cycles of recrimination, and the destruction of a previously-functioning society. The American patriots created, perhaps accidentally, new institutions that created more than was destroyed.*

Although Breen never references it, the American experience in Iraq and Afghanistan always hovers around this book, not least in the use of the word insurgents. In fact, from the title I expected a more revisionist book, one that applying theories of insurgency and counter-insurgency to understanding the Revolution. That's not what this book is, but the experience of the last eight years intrudes anyway, especially in the use of contemporary language such as "losing hearts and minds." In retrospect, one wonders whether the British could ever have reestablished control over the colonies, even if they succeeded in crushing Washington's army; they certainly could not afford to keep foreign mercenaries on permanent garrison from Massachusetts to South Carolina forever. We Americans like to boast of the long odds against us in the Revolution, but we've tried counter-insurgency from the other side, too, and it's harder than it looks. Killing enemy fighters and controlling the country are vastly different matters and I wonder if, had the American army dissolved at Valley Forge, the British would only have found themselves back in 1774 again.

_________________________________________

* Incidentally, Breen has compared our current Tea Partiers to their more orderly forebears and believes the latter were the better people.

Friday, September 3, 2010

Friday photo

Creeping socialism continues to destroy America. See it? Right in front of your eyes! The destruction of individualism and God-given capitalism is happening right now and only the most discerning Americans can recognize it!

In his 1887 book, Looking Backward, Edward Bellamy explained the crucial distinction between liberty and the socialist nightmare that he hoped to bring about. It's all about umbrellas:

A heavy rainstorm came up during the day, and I had concluded that the condition of the streets would be such that my hosts would have to give up the idea of going out to dinner, although the dining-hall I had understood to be quite near. I was much surprised when at the dinner hour the ladies appeared prepared to go out, but without either rubbers or umbrellas.

The mystery was explained when we found ourselves on the street, for a continuous waterproof covering had been let down so as to inclose the sidewalk and turn it into a well lighted and perfectly dry corridor, which was filled with a stream of ladies and gentlemen dressed for dinner. At the comers the entire open space was similarly roofed in. Edith Leete, with whom I walked, seemed much interested in learning what appeared to be entirely new to her, that in the stormy weather the streets of the Boston of my day had been impassable, except to persons protected by umbrellas, boots, and heavy clothing. "Were sidewalk coverings not used at all?" she asked. They were used, I explained, but in a scattered and utterly unsystematic way, being private enterprises. She said to me that at the present time all the streets were provided against inclement weather in the manner I saw, the apparatus being rolled out of the way when it was unnecessary. She intimated that it would be considered an extraordinary imbecility to permit the weather to have any effect on the social movements of the people.

Dr. Leete, who was walking ahead, overhearing something of our talk, turned to say that the difference between the age of individualism and that of concert was well characterized by the fact that, in the nineteenth century, when it rained, the people of Boston put up three hundred thousand umbrellas over as many heads, and in the twentieth century they put up one umbrella over all the heads.

As we walked on, Edith said, "The private umbrella is father's favorite figure to illustrate the old way when everybody lived for himself and his family. There is a nineteenth century painting at the Art Gallery representing a crowd of people in the rain, each one holding his umbrella over himself and his wife, and giving his neighbors the drippings, which he claims must have been meant by the artist as a satire on his times."

Now UM has replaced its puny little brick bus shelter with this grandiose abomination designed to coddle their students into accepting the nanny state and believing they don't need to take responsibility for keeping themselves dry. Can our final enslavement be far behind?

Monday, August 9, 2010

Atomic bombing anniversary

I notice a number of liberal bloggers referencing the Hiroshima bombing this past week. I'll just point to my review of Gar Alparovitz's The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb for my views on the topic.

I notice a number of liberal bloggers referencing the Hiroshima bombing this past week. I'll just point to my review of Gar Alparovitz's The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb for my views on the topic.

Thursday, July 22, 2010

Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue

I recently read John McWhorter's book Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue: The Untold Story of English, which is an excessively self-conscious revision of the history of the English language. Excessively self-conscious because McWhorter's jabs at the "history of English experts" quickly grow tiresome, and frankly make him sound like something of a crank - the sort of tone that creationists take towards scientists. But an interesting revision because he also explains why a different set of skills allows a different kind of linguist to see a different history to our language.

I recently read John McWhorter's book Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue: The Untold Story of English, which is an excessively self-conscious revision of the history of the English language. Excessively self-conscious because McWhorter's jabs at the "history of English experts" quickly grow tiresome, and frankly make him sound like something of a crank - the sort of tone that creationists take towards scientists. But an interesting revision because he also explains why a different set of skills allows a different kind of linguist to see a different history to our language.

The primary difference is that McWhorter doesn't specialize in a single language: he specializes in creoles, those curious half-and-half languages that arise when competing native languages occupy the same space. And he argues that English grammar displays the tell-tale signs of miscegenation, a salad bowl of features that tell the history of Angles and Saxons landing in Celt-occupied England in the 5th Century CE, the Viking invasion of same 300 years later, and the Norman conquest of 1066.

These incidents are well-known, of course, but McWhorter believes their effect on the people's speech is not. Traditionally, the Celtic language is believed to have gone extinct and been more or less completely replaced by the speech we know as Old English. The evidence is the extreme shortage of words in English that can be traced to Celtic origins - the subjugated Celts seem to have contributed almost nothing to the invaders' language. In my own linguistics class years ago, my instructor presented this as a mystery: the absence of Celtic words would suggest that the Celts were quickly killed off; however, the archaeological evidence didn't show an unusual amount of warfare and suggested a long period of coexistence. How to resolve the paradox?

The key to the puzzle may be to approach language with less attention to vocabulary and more attention to grammar. This is what McWhorter does. Throughout the book he displays a familiarity with a vast number of different grammars, especially the funky features that are rare and even unique to one language or another. And through grammar, he sees strong evidence that the Celts lived on for many years, kept their own language, and occasionally spoke English. When they did use English, they added a couple twists that seemed natural to themselves, but probably sounded quite strange to the Angles. Eventually, those oddities began to sound familiar and became the common way to speak.

One of these is the "meaningless do," the semantically pointless addition of "to do" in a sentence when we ask a question or state a negative. It's the reason why all other speakers of a Germanic language can say, "Read you the book?" and get the reply, "I read not the book," but if an English speaker tries that, he sounds like he's channeling Yoda (who, to be fair, did learn his English a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away1). The English speaker says, "Did you read the book?" and hears, "No, I didn't read the book." "Do" adds no meaning to the sentence, but it is necessary in order to be grammatically correct.

It's a weird construction because none of English's close relatives construct their questions and negatives this way. In fact, this sort of thing is rather rare across the globe. But there are a couple dead languages that are known to have used the meaningless do: Celtic and Welsh. The people who were ruled by invading Angles and Saxons, learned the invaders' language, but continued to speak their own at home. What are the odds that English picked up do from their subjects' language rather than inventing in de novo?2

The Vikings had a different effect on English, an effect that McWhorter describes as "battering" the grammar. If you've put some study into German, you know that its nouns and adjectives rarely appear in sentences as they do in the dictionary. Instead, they take all these damned endings: one of three different endings, depending on whether its gender is masculine, feminine, or neuter, and another for the plural. And each of these will change depending on whether the word is a subject, direct object, indirect object, or possessive. Germans don't seem to have trouble with it, but what a pain for the rest of us!

The Vikings found those endings to be a total pain, too. In fact, it appears that they couldn't get the hang of them at all and just ... dumped them. It must have been a horrid-sounding English to the natives, as horrible to them as it would be to me if someone relentlessly used -ed for every past tense (gived, throwed, hitted, etc.). But the Vikings came in waves of all-male groups, married local women, and raised children who heard this nasty tongue from their fathers, if not their mothers. The version without endings spread, across the country and through the generations. English differs from German today because, to some extent, we speak German like lazy, dumb foreigners.

These developments have been obscured because historical linguists tend to look at written texts for their evidence of past languages. And the written record doesn't seem to show these developments. But McWhorter's explanation is plausible enough: writing was uncommon, reserved for formal occasions, and deliberately preserved the ancient modes. The vernacular changed, but the professional scribes did not deign to record it.3

Then came the Normans. For 150 years, French was the lingua franca4 and the style of formal, written Old English was forgotten. When the English cast off French and returned to their native tongue, they began writing it as they spoke. Suddenly, Middle English enters the written record.

And the Norman influence on English? Although they wrote in French, there is documentary testimony that the Norman overlords were speaking more English than French. However, there were only few of them and they didn't mix with their subjects - their influence on English grammar was negligible. The language picked up an enormous number of French words -- it was written, not spoken, French that left its mark -- but this doesn't seem to interest McWhorter very much. He's much more interest in grammar than vocabulary.

At every turn, McWhorter's analysis of English's evolution is grounded in historical circumstance. The Celts added only a few subtle grammatic changes, a consequence of continuing their own speech apart from the English speakers, but over enough centuries to add a few distinctive constructs. The Vikings mixed with the local people, intermarrying and adopting the local language immediately - but badly, in a grammatically stripped-down form. And the Normans arrived in very small numbers, and remained a tiny elite, apart from the rest of the people; their written documents enriched English vocabulary, but left no mark on its grammar.

Finally, recall that McWhorter studies creoles, specializing in the mixing of languages. He has bones to pick with grammatical nitpickers, the sort who fret over split infinitives, prepositions at the end of sentences, who v. whom, or "He done read the book" (my example, not his). I don't know what he thinks of "refudiate," but you can almost hear him laughing at those prissy grammar Nazis5 who think they're speaking some sort of "pure" English, when in fact their speech is descended through a long line of folks who just didn't know how to talk good.

[Addendum]

As a followup to Heidi's comment, here's a map showing the maximum spread of the Celts. As you can see, they had a pretty wide influence in Europe, although not so much the Scandinavian countries:

_________________________________

1. Although Yoda, as I recall, sometimes uses "do" in the modern manner. He's had a long time to listen to those young Jedi.

2. The progressive "He is reading" is another form that existed in Celtic and today is peculiar to English.

3. It should be no surprise to academics. After all, they're the ones who have to teach their students "You don't write like you talk, dude, or your grade'll suck!"

4. Yes! Pun intended! Would you doubt me?

5. Which, yes, often describes me.

Monday, May 31, 2010

Book review: The Unlikely Disciple

Kevin Roose is the son of Quakers from Oberlin, Ohio, and was a student at Brown University when he decided to spend a semester at Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University. While his friends traveled to Europe for study abroad semesters, Roose decided try someplace more exotic still. He would go undercover at "America's Holiest University" and then write a book about it. So far outside his experience was the world of evangelical Protestantism, that his family and friends expressed the sort of fear you would expect if he were departing for Mogadishu.

Roose was well-advised to present himself as a newly-minted Christian, as evangelical culture was every bit as alien as he expected and it’s not easy to fake. Despite numerous faux pas, he managed to deflect suspicion just well enough to evade exposure. His unfamiliarity with the Bible not only threatened to give him away, but it made his Theology and Old Testament Studies classes surprisingly difficult.

Theology and Old Testament Studies had some genuine academic content, but other classes were pure religious, cultural, and political propaganda. His History of Life class was nothing but a recitation of Young Earth Creationism claims, delivered by a Dr. James Dekker who sported a white lab coat and pointedly announced, “I am a real scientist!” (Roose says that Dekker has done some work in neuroscience, but my Web of Science search didn’t turn up any hits for him) Exams include questions such as “True or False: Evolution can be proven using the scientific method.”*

The GNED II course was unvarnished indoctrination into the right wing political opinion. About this, Roose says, “At first, I couldn’t believe Liberty actually had a course that teaches students how to condemn homosexuals and combat feminism. GNED II is the class a liberal secularist would invent if he were trying to satirize a Liberty education. It’s as if Brown offered a course called Godless Hedonism 101: How to Smoke Pot, Cross-dress, and Lose Your Morals. But unlike that course, GNED II actually exists.”

Roose is closer to the mark here than he probably realizes. Many evangelicals do rather believe that secular university professors creates course content by thinking, "What would seduce students away from the Church? Let's teach that!" Just as many conservatives believe that Fox News is no more biased than the "mainstream media," they believe that relentless propaganda is merely a mirror image of secular education. This is, of course,yet another manifestation of the Paranoid Style.

"The Liberty Way" is all about rules**, covering everything a religious conservative worries about: no visitation to opposite sex dorms, no kissing, and no hugging for more than three seconds. Holding hands is okay, but alcohol and R-rated movies are forbidden. No shorts, no jeans with holes, for men no shirts without collars (you have to have a collar, so they can tell your hair isn’t long enough to touch it). Rooms are inspected three times a week and you cannot spend the night off campus without written permission. Reprimands, and even monetary fines, keep the miscreants in check. Roose gets fined for falling asleep during church.

It may sound like prison, but for devout students it's an effective path to true liberty (thus the school's name). It's the Fifth Freedom, the Freedom from Distraction - here in the cocoon, you can concentrate on God instead of sex and parties. That cocoon is so essential to maintaining the "Liberty Way" that some students rather dread the summer break, when they have to leave the cocoon and fend for themselves, with only God to help them. "I'm scare I won't be able to keep this up over the summer," one friend confides to him, afraid he won't be able to maintain his level of religious commitment when he's no longer subject to so much social control.

That inability to succeed with only God's help is a contradiction at the heart of evangelical religion that I've never been able to get over, and one that Liberty demonstrates in spades: faith is maintained almost entirely by social pressure, and very little by the power of God himself. Tell an evangelical minister that you don't need the church because you commune directly with God and his first order of business will be to convince you that your spiritual journey requires a professional navigator and that he's there to plot your course for you.

Nowhere is this more evident than with that intractable problem, masturbation (and its evil ally, pornography). There are counselors on campus to help students fight the temptation, and there are strategies for resisting temptation. Those strategies consist mainly of making sure you're never entirely alone and you might get found out if you misbehave. Turn your bed so that your computer screen faces the door, and leave that door open to all passersby. Some kids even go so far as to sign up with a service called X3Watch, which sends a copy of your browsing history to designated supervisors - their parents, maybe, or more often their pastor. It's not so much self-control as it is a commitment to eternal supervision.

That need for human surveillance strikes me as odd, because you're supposed to believe that God is watching you every minute. Somehow, the certainty of divine observation has almost no force at all compared to even a slight possibility that someone you know will see you misbehaving. The internet has exposed this dirty little secret: upstanding Christians, even many pastors, who would never risk being seen entering a porn shop can't keep their browsers off the porn sites. How deeply can even a pastor believe in an omnipresent God if God's presence has less influence over his behavior than the possibility that his wife or kids could come home at any moment?

As Roose self-reports, the bubble was so enveloping that he became partially assimilated himself. He experienced the contagion of religious ecstasy. He began to enjoy church for the camaraderie, as a gathering of his friends, but kept enough awareness to realize that the camaraderie was the bait and religion the hook. Come for the friendship, absorb the dogma. It's not that he started to believe in fundamentalist religion - but he began to forget how ludicrous it all is.

Roose writes surprisingly well (he was only 19 at the time) and, more importantly, learns genuine affection and respect for most of his dorm mates. In many respects, they’re not much different from other college students – except they may be even more sex-obsessed than kids who occasionally get a little action. Their attitudes toward religion, the Bible, and Jesus don’t offend him, but the relentless homophobia does. He finds himself quietly enraged at the way his dorm mates casually throw out the epithet “faggot.” But he also becomes numb to it, and worries that his outrage may be diminishing (Roose has gay relatives, so it's a particularly salient issue).

He finds some reassurance in his dormmates' reaction to Henry, an older student who is exceptionally homophobic and patriarchal. At one point Henry angrily announces, "If my wife ever cuts her hair, she'll learn about submission to her husband." Eventually, Henry acquires the delusion that the majority of his dormmates, and Roose in particular, are gay, and seems almost on the verge of violence. Roose is unsure what to make of Henry. On the one hand, it's a useful reminder that however unserious his friends might seem when they throw out the word "faggot," Christian homophobia is real, intense, and its effects on real people is no joke. On the other hand, no one likes Henry, because even at Liberty University, being a Christian is not as important as just not being an asshole. Dogma does not entirely override the instinct for human decency.

Roose has two reasons for being hopeful about the graduates of Liberty University. One is that he has met a few students who are open-minded, questioning, and critical of the regimentation they experienced at Liberty. He hopes that exposure to the wide world will undo some of the spell that Liberty has woven around them. Second, to be a legitimate university, Liberty has to hire faculty with Ph.D.'s, and some of these long to be doing the sort of work that a real university, not a brainwashing facility, does. They want to be real professors and in time they might gain some influence in that direction.

In short, Roose has faith in the temptations of conventionality in shaping religion and religious people. I'm not sure he knows enough religious history to appreciate how strong that tendency is, but it's a well-founded hope. As much as religious leaders like to imagine themselves standing up to the world, in the end they can only maintain their position by riding the cultural current. One of Roose's friends, who has given extra study to Jerry Falwell, concludes bitterly that while Falwell had toned down his racism in his latter years, he probably hadn't changed his attitudes - he just knew he couldn't remain respectable saying what he really believed.

But it cuts both ways. Religion will conform to the cultural norms it no longer has any hope of undoing. But his friends may also become more conventional, and less open-minded, as they leave youth and approach middle age. Much depends on what passes for conventionality in 10-15 years; let's hope it's a less fearful and authoritarian style than is conventional among the people who support Liberty University nowadays.

____________________________________

* Roose provides a sample quiz at his web site. I got a perfect score; how 'bout you?

** Apparently Liberty doesn't want just anyone to know what those rules are - you need a password just to read the Code of Conduct at their website!

Monday, May 24, 2010

Mark Twain speaks!

Mark Twain's autobiography, which he instructed should remain unpublished until 100 years after his death, is coming out this fall! It should be worth the wait.

Why the long delay? Apparently, Twain spoke/wrote rather freely about certain people. Also, he knew some of his views would be unpopular:

"He had doubts about God, and in the autobiography, he questions the imperial mission of the US in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. He's also critical of [Theodore] Roosevelt, and takes the view that patriotism was the last refuge of the scoundrel. Twain also disliked sending Christian missionaries to Africa. He said they had enough business to be getting on with at home: with lynching going on in the South, he thought they should try to convert the heathens down there."

If he thought that the US of a hundred years later would agree with him, he badly miscalculated. If he thought we would need to hear this just as much now as in his day, he was remarkably prescient.

(Via Record and Archives in the News)

Labels:

books,

culture,

literature

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Thursday, January 28, 2010

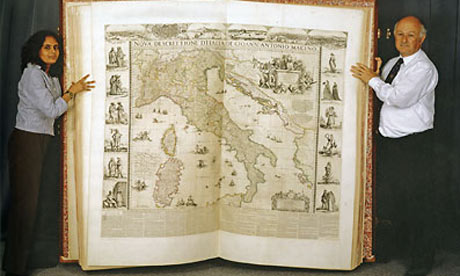

Largest book in the world goes on show for the first time "It takes six people to lift it and has been recorded as the largest book in the world, yet the splendid Klencke Atlas, presented to Charles II on his restoration and now 350 years old, has never been publicly displayed with its pages open."

"It takes six people to lift it and has been recorded as the largest book in the world, yet the splendid Klencke Atlas, presented to Charles II on his restoration and now 350 years old, has never been publicly displayed with its pages open."

I might have written "therefore" rather than "yet."

Via the Maps-L listserv

Labels:

Archives,

books,

cartography

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Sunday, January 10, 2010

Is the Kindle succeeding?

Via The Scholarly Kitchen:

Doing the Kindle Math — Does Amazon’s Opacity Conceal a Shameful Truth?

[V]ery few have seen fit to question the actual success of the current market leader, Amazon’s Kindle. That may be changing, as Amazon’s steadfast refusal to release sales figures and reliance on convoluted statistics is wearing thin. Blogger Mike Cane has gone so far as to call the Kindle “an outright fraud”.... Cane has called on publishers to start releasing e-book sales numbers, and suggests we’re going to be shocked at how low they are.

Labels:

books,

commerce,

publishing

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Thursday, December 17, 2009

Finding a use for the National Union Catalogue

What do you do if you have hundred of green-covered books that are hopelessly obsolete? You build a Christmas tree!

What do you do if you have hundred of green-covered books that are hopelessly obsolete? You build a Christmas tree!

Via librarian.net

Saturday, November 14, 2009

The Little Leather Library

A few months ago, I found a set of miniature books at Mom's house that looked rather old and which I don't recall ever seeing before. They were sitting in the garage, which has the typical lack of climate-control - so I brought them home for better care.

A few months ago, I found a set of miniature books at Mom's house that looked rather old and which I don't recall ever seeing before. They were sitting in the garage, which has the typical lack of climate-control - so I brought them home for better care.

They turned out to be a set of books from the Little Leather Library, which published over a hundred classic titles from about 1916-1926. The brown book in the photo is one of the earlier editions, but the rest (with the green covers) would date from between 1920-1924. I had imagined that Mom's parents bought these for their kids sometime while they were growing up, but they actually predate her parents' marriage in 1925.

I don't know  whether it was my grandmother or grandfather who bought them, but they would have been affordable to a young adult or a newlywed couple. They were mainly sold in sets, at prices that came to about 10¢ per copy. Early editions were sold through Woolworths department stores, but later they were marketed directly through the mail. I expect these were a set, because otherwise it's hard to imagine my conservative grandparents choosing two Oscar Wilde titles. LLL also published many books of the Bible, but grandma and grandpa would have already had Bibles.

whether it was my grandmother or grandfather who bought them, but they would have been affordable to a young adult or a newlywed couple. They were mainly sold in sets, at prices that came to about 10¢ per copy. Early editions were sold through Woolworths department stores, but later they were marketed directly through the mail. I expect these were a set, because otherwise it's hard to imagine my conservative grandparents choosing two Oscar Wilde titles. LLL also published many books of the Bible, but grandma and grandpa would have already had Bibles.

The Little Leather Library was all about bringing classic literature to the masses, at as cheap a price as possible. Classic literature, of course, meant out-of-copyright, royalty-free literature; to further reduce costs, the original leather covers were quickly replaced by cheaper synthetic covers. However, the expensive look remained, as the publishers understood that middle America not only wanted good literature to read, but wanted nice things to display in their homes. One of the publishers even later coined the term "furniture books" to describe volumes which sold on appearance as much as literary content.* Their success can be gauged by the fact that the little books aren't rare: you can find them on E-Bay for about $3-4 dollars per book.

As a point of interest, LLL founder Albert Boni went on to found the Modern Library; the men who bought the company from him, Harry Scherman and Maxwell Sackheim, later started the Book-of-the-Month Club.

For more, see Janice A. Radway, A Feeling for Books: the Book-of-the-Month Club, Literary Taste, and Middle-Class Desire , or Little Leather Library

Titles:

Robert Browning, Poems and Plays

Robert Burns, Poems and Songs

Samuel T. Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Other Poems

W.S. Gilbert, The "Bab" Ballads

Abraham Lincoln, Speeches and Addresses

Thomas Babington Macauley, Lays of Ancient Rome

Thomas Babington Macauley, Lays of Ancient Rome (misidentified on the cover as Longfellow's Courtship of Miles Standish)

Maurice Maeterlinck, Pelleas and Melisande

Olive Schreiner, Dreams

William Shakespeare, The Tempest

Alfred Lord Tennyson, Enoch Arden and other Poems

Henry David Thoreau, Friendship and other Essays

George Washington, Speeches and Letters

Oscar Wilde, Ballad of Reading Gaol and other Peoms

Oscar Wilde, Salomé

Multiple authors, Fifty Best Poems of America

_________________

* No to accuse my grandparents of mere pretension, however. Grandma was the daughter of a newspaper publisher and raised a family that valued education.

Labels:

books,

commerce,

literature,

material culture

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

Mapping banned books

From the Maps listserv, here's a Google Maps plotting of banned books ( as compiled from the ALA's "Books Banned and Challenged 2007-2008," and "Books Banned and Challenged 2008-2009," and the "Kids' Right to Read Project Report"). How does your neighborhood compare?

I notice that not every item on the source lists seems to be plotted, so maybe Utah isn't as clean as it looks. Still ... didn't you think there'd be a few markers there? Maybe I should give more credit where credit is due.

Despite a certain incompleteness, someone has made the map pretty informative. As you mouse over the markers, it pops open some copied-and-pasted text that describes the incident behind the listing. Some of the usual suspects are there, including Philip Pullman and JK Rowling; also, someone considered Craig Thompson's Blankets too sexy and had it moved from a young adults section. Someone else thinks Of Mice and Men is an offensive load of crap and shouldn't be read. In general, bad books are those that mention sex, contain swear words, and don't flatter Christianity.

Of course, I'm not always completely on-board with the banned books lists, as they tend to lump every type of "challenge" together in a single category. Some parents question whether a books is age-appropriate, not whether it has any value. I might disagree, but it's a fair question.

I'm also slightly open to complaining when books are assigned reading. I'm not really opposed to children being forced required to read things they might not otherwise encounter, but even a schoolteacher doesn't have complete authority to override parental wishes. I think it's a bad impulse to complain - giving a child a book is not an effective brainwashing technique, but shielding them from any message but your own is. So I disapprove , but the parents aren't necessarily outside their rights.

Then there are the demands that books be removed from library shelves. That's entirely wrong, period. You don't have the right to demand that no one else's child be allowed to read a book.

Labels:

books,

cartography,

censorship

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, September 25, 2009

More trouble for the Google Books settlement

French publishers have brought suit in Paris to stop the Google settlement, because the newly-digitized collection certainly contains many French works without their publishers' permission. The rhetoric is a wee bit hyperbolic: the president of the publishers group Syndicat National de l’Edition refers to the settlement as a "cultural rape," from which you would think scanning books is comparable to, oh, Napoleon filling the Louvre with the pillaged treasures of Europe or something. Ridiculous.

I had to search several articles before I could discover that Google is scanning books from a French library, which is the only avenue I can see for thinking French courts would have any jurisdiction at all; my (shallow) understanding of the Berne Convention is that French books in America fall under American law (the main point of the convention is that they do get the protection of the other country's laws and are not fair game for plagiarism and republishing). So I dunno - it might be a stretch to have Paris courts weighing in on the settlement. But in any event, the challenges are mounting and we may be much farther from that wonderful electronic library than we need to be.

Labels:

books,

copyright,

intellectual property,

law,

libraries,

technology

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, September 11, 2009

Copyright Office weighs in on Google settlement - not good

The Register of Copyrights, Marybeth Peters, testified before the House Judiciary Committee yesterday and she is quite skeptical about the legality of Google's plan to scan books and create a registry of authors for future compensation. The crux of her concern:

Ms. Peters said that in granting something like a “compulsory license,” a requirement that rights owners license works to others, the settlement essentially usurped the authority of Congress and skirted deliberations.

“In essence, the proposed settlement would give Google a license to infringe first and ask questions later, under the imprimatur of the court,” Ms. Peters wrote in her prepared testimony.

This has always been the biggest legal sticking point in Google's digitization scheme - do they need to negotiate approval first (the opt-in position), or can they go ahead with their scanning and then later restrict books whose rights-holders step up and ask them to stop (the opt-out position). Getting prior permission for millions of books is impractical, to say the least, so Google has always preferred opt-out: we'll scan it, but let us know if you don't want us making it available.*

Peters is arguing that, practicality be damned, the law just doesn't allow it. Like it or not, you need permission first.** The Google registry essentially creates a compulsory license system, much like how songwriters get paid but can't make a radio station stop playing their songs. The latter system, of course, came about by an act of Congress and there's the rub - Google isn't Congress, even if they do have a stronger bank account.

You can read my contemptuous views on the so-called Google "monopoly" here, but the registry is a more serious matter. Even if it's a good solution - and I believe, for the most part, it is - it might not be legal without federal legislation. Unfortunately, so long as it appears only one company is in a position to benefit, that won't happen. Amazon may be building a digital library under an opt-in system, but that leaves an enormous amount of literature - the orphan works - untouchable.

So it's entirely possible that, while there's no illegal monopoly here, the fear of one will prevent an allowable solution - Congress stepping in and creating a compulsory licensing scheme. It will be a tragedy if we lose a chance to make all these books accessible because only one company was bold enough to take on the task***, but that could well be the result. Is it really better to have no grand digital library than to let Google be the spearhead?

___________________

* Where major publishers are aware of what's going on, though, they don't hesitate to opt-out before the scanning takes place. At the UM libraries, the stacks are festooned with pink slips that read "Not scanned at publisher request."

**Unless, like Bobby Bowfinger, you're lucky enough to catch those publisher in some kind of embarrassing situation....

***Ayn Rand fan should be hearing, "Why should only Henry Rearden be allowed to make Rearden Metal?" Seriously, I've seen suggestions that Google should be forced to give away all the digital files they've made at enormous cost.

Labels:

books,

copyright,

intellectual property,

law

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Sunday, August 30, 2009

Monday, August 24, 2009

In which Microsoft makes me giggle

Microsoft, Amazon, and Yahoo have teamed up to form something called the "Open Books Alliance" to oppose the Google Books settlement. You can read about it here.

"Open Books Alliance." At least they got that last part right. But it's worth noting that Microsoft is the only one who has been in the book digitizing business and they quit when they couldn't figure out how to make money at it. Now they say it's unfair that someone with a better business model will have an advantage over their own inferior business model. Yes, exactly. Free enterprise is supposed to work that way.

Let me repeat it again: Google is the only one doing this because they're currently the only ones who have both the desire and the financial incentive to do so. That's not a monopoly, at least not in any restraint-of-trade sense.

I suppose I can understand MS's confusion, though - it's a novelty for them to be on this side of a monopoly complaint.

Monday, March 30, 2009

Wicked

I've always enjoyed re-imaginings of well-known tales, familiar stories told from an utterly unfamiliar point of view. Marion Zimmer Bradley's The Mists of Avalon may have been my introduction to the genre, I can't quite remember, but I still recall my astonishment at how a completely original tale could be woven out of those old legends and I could be made to think, yes, this is how it might really have happened.* So last weekend, when Heather mentioned Gregory Maguire's Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, I decided I needed to read it. That was a good move.

So last weekend, when Heather mentioned Gregory Maguire's Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, I decided I needed to read it. That was a good move.

In a way, the book was not quite what I expected. I anticipated a more complete reversal, a story where the Witch was really the good person through to the end. Maguire, on the other hand, has said that he intended to write a story where the Witch was really evil throughout. What emerged was something in between, and therefore far more interesting. His Witch, Elphaba (a play off "L. Frank Baum"), is a woman who was early alienated from most of her fellow humans, made it her cause to fight evil (which the Wizard of Oz proves himself to be), but found that evil seemed to be winning every round -- and that all too often it was her own efforts that ended up contributing to tragedy.

Although never really a sweet or generous person, Elphaba is smart, principled, and mostly admirable. By the end of the book (Dorothy and her annoying little dog don't even show up until the last section), as her bitterness has grown and festered, the Witch is not a person who desire to perform evil, but she's even less nice and plays the part of a wicked witch convincingly enough. To the extent that she remains sympathetic, it's as a tragic figure: you've long stopped admiring her behavior, but you never wanted to see her become so unlikable.

If Tolkien thought that the will to dominate was the source of evil, Maguire reminds us that watching evil triumph can be a most embittering experience, leading an otherwise good person to wicked behaviors of their own. A timely lesson, too, in this era of Culture Wars, where both sides see wickedness on the march and are tempted to despair.

_______________________

* Cynicism helps; from an early age I found it easy to believe that the standard tales might really be self-serving propaganda and that there could be another side to the story.

Labels:

books,

culture,

literature,

morality

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Saturday, November 15, 2008

Book review

If you want to pick a fight with a medievalist, you can always start by dropping the phrase "Dark Ages." So along comes the classicist Charles Freeman, whose The Closing of the Western Mind argues that the Christian era really did represent a sort of dark age, as faith-based theology put an end to the Greek tradition of rational thought.

If you want to pick a fight with a medievalist, you can always start by dropping the phrase "Dark Ages." So along comes the classicist Charles Freeman, whose The Closing of the Western Mind argues that the Christian era really did represent a sort of dark age, as faith-based theology put an end to the Greek tradition of rational thought.

Freeman argues that, while it is true that the high point of Greek rational thought had passed by the time Christianity arrived on the scene, it was not entirely dead yet. Although they based their theories on erroneous conceptions of the world, the astronomer Ptolemy and the physician Galen were still trying to apply reason to the observation of the natural world. In the Western world, however, both Ptolemy and Galen came too be regarded as unchallengeable authorities and there was no improvement upon their work for over a thousand years. Seriously - a thousand years of no progress in either astronomy or medicine. What went wrong?

In Freeman's telling, an unfortunate combination of events. First, Christianity fell under the influence of the Apostle Paul, who explicitly rejected rational thought and Greek philosophy (although he mimics their style - Paul sounds more like a Greek than he does an Ezekiel of a Jeremiah); it may also be no coincidence that Paul's writing is obsessed with justifying his dubious claims to authority. Paul was at odds with everyone, and so were the other early Christians, who made themselves obnoxious to Jews and Romans alike by refusing to do their civic duty to any other gods.

As Christianity spread, this contrarian spirit became more difficult to deal with. Persecutions ensued, without ultimate success. The emperor Constantine, trying to bring a little peace and quiet to the messy empire, decreed an end to religious persecution and legalized Christianity, along with all other religions/cults.* It was only then that Constantine discovered how bitterly divided Christians were over obscure points of doctrine. If the difference between Heaven and Hell weren't enough incentive to get it right, now there were large sums of imperial money to be had for the winners in these disputes. The Council at Nicaea in A.D. 325 didn't bring unity, but it did establish a tradition of secular authorities bringing ecumenical councils together and then choosing who would be the orthodoxy.

Doctrinal disputes continued, however, and they were fundamentally unresolvable by any kind of rational thought. The essential problem was that the theologians were arguing over things for which there was no particular evidence. Freeman points to the Trinity, for which there is no direct Scriptural support; the concept has to be teased out of writings by authors who aren't very clear on the subject - because they didn't know anyone would ever be discussing it. John's Gospel insists that Jesus was God, but the Synoptic Gospels say no such thing and seem to provide a lot of hints to the contrary. While the Greeks had recognized that the nature of the gods was unknowable, the Christians were obsessed with establishing unknowable things with certainty.**

Eventually, argumentation had to be suppressed altogether. Thus the rise of faith, which in practice meant uncritically accepting the authority of the Church.*** Although he doesn't say it as explicitly as this, this is what Freeman means by the word faith: it's really all about authority. In the ancient Greek world of squabbling city-states, thinkers could freely challenge those who had come before. No such thing occurred in the ancient Babylonian or Egyptian empires and the Roman emperors were equally comfortable with using their authority to define the truth. The centralized Church that inherited the Western empire stepped into the role as naturally as if they'd been born to it.

* Constantine did not actually make Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. He put an end to official persecutions and built impressive churches in the time-honored manner of imperial patronage. Generally, the Romans would let you believe anything you wanted, so long as you didn't piss off the other gods by refusing to make the expected sacrifices; if you didn't, it made you a threat to public order and they dealt harshly with that.

** It's not coincidental that Christian theologians followed Plato and suppressed Aristotle. Plato's theory of Forms asserted a transcendent reality, which fit neatly with the Christian view of God, but likewise assumed that studying the physical world was no way to study reality. In The Republic, Plato says, "We shall approach astronomy, as we do geometry, by way of problems, and ignore what is in the sky if we want to get a real grasp of astronomy."

*** That is, when there was no longer an emperor to decree these things. By that time, the Church had long been thoroughly intertwined with the political power structure and the aristocracy was deeply embedded in the Church hierarchy.

Wednesday, August 6, 2008

Bookstores

Richard Cohen weighs in on the decline of books as the essential means of reading:

It's really tough being a book lover in a digitized world

But then there's this paragraph:

I never buy from Amazon unless I have to. I buy from actual bookstores. You go there and people are browsing or having coffee or staring into open laptops and pretending they're writers or something.

What!? You still find people in bookstores? Then what's the #v*%ing problem? I love books, too, but sometimes the medium is not the message. As long as reading remains vibrant, I don't care how it's being done.

Labels:

books,

material culture

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

Books - the atomic bombs

It's been sitting on my shelf for years, but I finally read Gar Alperovitz's The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb. I'm regret letting it wait so long, since the book is as close to a definitive word on the subject as we're likely to see unless important new evidence emerges.

It's been sitting on my shelf for years, but I finally read Gar Alperovitz's The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb. I'm regret letting it wait so long, since the book is as close to a definitive word on the subject as we're likely to see unless important new evidence emerges.

Alperovitz produces the documentary evidence to prove that Truman and other US leaders knew that Japan was on the verge of collapse, that the Japanese' worst nightmare was about to come true (Russia was entering the war against them), and that the Japanese were looking for a way to surrender. American military leaders fully believed that Japan had little chance of holding out until an invasion began (still seven months away), let alone resisting long after. Despite this conviction, they used atomic bombs to destroy not one, but two cities, deliberately targeting civilian populations rather than military installations. This much is really not arguable.

They believed that Japanese leaders needed a major shock to convince them to quit, but had expected all along that the Russian attack would do the trick. But here was the dilemma: the Russians could hasten the end of the war, but they also strengthen their position in Asia after the war. Soviet-American rivalry was already in motion. Alperovitz believes that the bombings were meant to make sure the Japanese surrendered ASAP - not just before the Americans had to invade, but before the Russians could have much to do with it. Also, a truly horrific display was expected to impress Stalin tremendously, perhaps making him a little more tractable later on.

Alperovitz believes the last factor - scaring the Russians - was a huge factor, because it's otherwise hard to explain why the Americans deliberately made it harder for the Japanese to surrender earlier. While Japan would have liked to hold onto any part of their mainland conquests, if possible, they were ready to give up all but one thing - they would not let the Americans depose Hirohito, especially when they could see what was about to happen to defeated German leaders at Nuremberg. All of the well-known talk of Japanese fighting to the last man was predicated on this belief that they would be fighting to protect their emperor. On the other hand, the one authority who could compel Japanese soldiers to lay down arms was, of course, the emperor.

Thus, it seems perverse that the Potsdam Declaration demanded "unconditional surrender" with no guarantee for the emperor. Nor was it an oversight: the language of such a guarantee was removed from the final draft of the Declaration. The Japanese asked for clarifications, but didn't receive any and didn't believe they could consider surrender under those circumstances. Eventually, of course, the emperor was retained, he did order his people to surrender, and they did. Considering that Hirohito had already initiated peace feelers through the USSR (before the Russians declared war themselves), and that the Americans knew all about it, Alperovitz provocatively suggests that the decision to use the bombs might have actually prolonged the war by a few weeks.

After the bombings, in response to a fairly small number of critical voices, Alperovitz argues that a myth of military necessity was consciously constructed to protect the American reputation (sound familiar? retain the moral high ground by controlling the story, not by restraining your actions). The famous figure of 1,000,000 lives saved by the bombings come from these actions - there is no documentary support for such an analysis anywhere and actual contemporary documents argue explicitly against the likelihood of so many casualties. Several of the top brass were quite straightforward (although not especially loud) in stating that the bombs made little or no contribution to the end of the war. But after Secretary of War Henry Stimson was convinced to put his name to a 1947 article inHarper's arguing otherwise, then the matter was settled for most Americans. Alperovitz devotes almost half of his 800-page book to this Myth-making effort.

As a PS, finishing the book provoked me to watch "Tora! Tora! Tora!" again last night and it's still an excellent work. A joint US-Japanese effort that doesn't seem to grind many axes, it rises above some rather pedestrian acting and tells an extremely compelling story. All without a dramatic musical score, too.