Friday, December 31, 2010

Friday photo

'Cause it's just too pwecious, idn't it?

A few years ago, my Mom and her neighbors were feeding three or four cats. Now there are a dozen of them, because cats aren't all that different from birds and bees. I have it on good academic authority that this cannot end well.

Labels:

animals

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Questions that arose while offline

I'm back from the finals of the Great Lakes Invitational hockey tournament in Detroit, where the University of Michigan bested Colorado College 6-5 in a sloppy, but dramatic, game. UM scored the first goal just half a minute into the game and later went up 2-0, then let Colorado College tie the game by the end of the first period. Trailing the Wolverines 4-3 entering the third period, the Tigers scored two goals to take a 5-4 lead and make the home fans squirm in their seats. But fickle Fortuna gave Michigan a pair of late goals, with six and four minutes left in the game, reversing the outcome and filling Joe Louis Arena with great joy and relief. Sports are such a strain on the soul.

While watching the game, several questions came up in conversation and no answers were available until I could get home and access the invaluable Wikipedia. So here, for no particular reason, are answers relating to a pair of random hockey questions:

* The Joe Louis Arena was constructed in 1979 and seats 20,000 spectators.

* We all know that the Original Six hockey teams in the NHL are the Boston Bruins, Chicago Black Hawks, Detroit Red Wings, Montreal Canadiens, New York Rangers and Toronto Maple Leafs. The next six? The Los Angeles Kings, Minnesota North Stars, Philadelphia Flyers, Pittsburgh Penguins, Oakland Seals, and St. Louis Blues, who all joined for the 1967-68 season.

* The first indoor hockey game was played in -- are you ready for this? -- 1875, in Montreal. In one crucial respect, it was even the first true hockey game: the puck was invented just for this match! Hockey was still played with a ball, but there were concerns over spectator safety. So the ball was replaced by a flat block of wood that, it was reasoned, would stay down on the ice (on Thursday night, one puck flew high enough to clear the tall net at the end of the rink, to the complete astonishment of a young first-time spectator behind me).  Also surprising is learning that, while popular in New England, hockey wasn't much known in Canada at the time. Who would guess such a thing? And curling was invented in Scotland - all the great Canadian games turn out to be imports!

Also surprising is learning that, while popular in New England, hockey wasn't much known in Canada at the time. Who would guess such a thing? And curling was invented in Scotland - all the great Canadian games turn out to be imports!

Labels:

sports

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

Hooray for True Grit!

I don't do movie reviews and I don't consider myself anything of a movie critic. I don't know movies, but I know what I like and I don't even know what I like. I know what I hate, though, which often turns out to be historical fiction. They never get it right, never resemble anything but modern day folks in outdated clothing. How often do you see someone spend millions of dollars researching and recreating, say, a ship from a century ago, but fail to create a single character who seems to belong in that era. Or present me with Roman senators pining for democracy.* Or not even try that hard, ending up with a Western that does ... ugh, this.

The dialogue is usually the worst offender. Inevitably, 'historic' characters will speak in modern colloquialisms, as grating to me as if a crew member walked in front of the camera and no one yelled "Cut".** Producers spend millions researching costumes, but almost never pay a historian to review the script and say, "No, stop, they just didn't talk like this in the 19th Century. Read some books and speeches from the time period and get an idea of how people spoke then."

Generally, the best way to capture a previous time period is to use a contemporary book. It's why adaptations of Jane Austen always conjure up their period better than anything written by a modern screenwriter. Modern writers just don't realize that "the past is a foreign country; they do things differently there."

However, I thoroughly enjoyed the Coen brothers' remake of True Grit. Not a modern coinage to be heard! The early scenes in Fort Smith are really one of the best representation of 19th Century westerners that I've ever seen. The actors all delivered their lines with an admirable naturalism that had me thinking, I'm really in Arkansas in the 1880's. The only fault is the impression that English speakers used no contractions a hundred years ago; they did. But if the dialogue sometimes seems slightly forced, it's never laid on so thick as the North Dakota dialect in Fargo.

The character actors populating Fort Smith actually outshine the big money stars in this regard. Jeff Bridges performs well, but gets some assistance from his character's gruff mannerisms; it works for him to sound a little stiff and self-aware. Matt Damon, unfortunately, never does manage to sound like he's doing aught but reading lines, and Josh Brolin does only slightly better. Hailee Steinfeld is amazing. Like Bridges, she gains an advantage from Mattie Ross's cold determination, so that it's appropriate if she never sounds entirely at ease. Nonetheless, I could easily believe she grew up speaking the way her character does. This film was a treat for the ears.

___________________________________________

* I saw Gladiator for entertainment relief after driving 2 hours to Bozeman for a dental appointment on my only day off during a two-week stretch. One of the worst days of my life.

** One of the all time worst: a 14th Century bishop saying, "I believe in miracles. It's part of my job."

Labels:

theater

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

That's snow!

Seventeen meters of snow in the mountains on Honshu:

Via Why Evolution is True

Labels:

nature

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Saturday, December 25, 2010

Friday photo, Christmas Eve edition

Awesome Christmas! A huge drum and a sand-bucket helmet! I bet your haul isn't half as good, but have a Merry Christmas nonetheless.

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

Imitators of Pilate?

At Slate, Kathryn Schulz interviews Josh Stieber, a man who entered the military as a militaristic Christian and became a conscientious objector. What his conscience objected to was actions like this:

There's really no way to defend yourself against a sniper shot or a roadside bomb, so some of our leaders felt that the only way we could defend ourselves was to intimidate the local population into preventing the violence in the first place. So our battalion commanders gave the order that every time a bomb went off, we were entitled to open fire on whoever was standing around. The way I interpreted that was that we were told to out-terrorize the terrorists.

Stieber is far from abandoning his Christian values. He takes them seriously, so seriously that he can't ignore or rationalize the contradictions between military action and Christian ethics. That makes Stieber a rare bird. One of his hometown buddies, in the same unit in Iraq, shocked him by describing the abuse he wanted to perpetrate on an Iraqi prisoner. When Stieber challenged him on the the contradiction to American principles, his friend replied, "No, he's Iraqi, he's part of the problem, he's guilty," and reaffirmed his desire to torture the man. Stieber escalated his critique - what about the Christian values of loving one's enemy and returning good for evil? "My friend said, 'I think that Jesus would have turned his cheek once or twice but he never would have let anyone punk him around.' "

It's as fine an example of cognitive dissonance as you'll ever see. Jesus, who allowed himself to be arrested, rebuked the disciple who tried to defend him, offered no defense during his trial, and allowed himself to be crucified even though innocent*, is now a tough guy who'll show a little token patience and then deliver the hammer. Yes, it's easier to redefine Jesus and contradict his clear representation in the Bible than to admit that you're contradicting your (stated, not felt) morality. Even if you have to turn Jesus into a Pontius Pilate. Alas, Stieber is the exception and his friend is the rule, as he discovered when he explained himself to his family:

I think a lot of what I've done has been a manifestation of those values, and to see the people who taught them to me enact them in such different ways, or at times it seems other things have taken priority over those values -- that can be challenging. Of all the people in the world who should see things the same way I do, who should be passionate about the same things I am and offended by the same things I am, it would make sense that it would be the people who taught me to think this way. When that's not the case, that can be very hard.

To their credit, his family accepted Stieber's decision, but they don't understand it -- even though it's the logical, perhaps inevitable, consequence of taking New Testament ethics seriously. For a certain strain of Christian, imitating Christ is literally incomprehensible. Fortunately, there are a few serious people like Josh Stieber who take ethics seriously, who understand morality as something to govern their own actions and not as just a club to compel obedience from others.

____________________________________

* Innocent by our lights, anyhow. By the standards of the Roman Empire, Jesus had indeed committed a capital offense: he was a no-account yokel who was disturbing respectable folks. Which makes him somewhat comparable to, say, illegal immigrants or Muslims in certain American municipalities today.

Monday, December 20, 2010

Interesting documents

[While I'm cleaning up my unpublished posts....]

Even the underworld needs accountants:

Via BoingBoing

Copyrighting T-Rex?

Here's an interesting case I started to write about, and then forgot to finish. But I'm still going to keep an eye on it. The Black Hills Institute of Geological Research is a private company in South Dakota that specializes in selling prepared fossils and casts. They claim that they loaned some Tyrannosaur bone casts to a Montana company called Fort Peck Paleontology, who never returned them and has been selling their own copies of these casts. BHIGR is suing.

Now I don't know what the terms of the loan were, and since BHIGR is a professional and commercial operation, you'd think they would write these restrictions into any contract they made. If they didn't, that's their mistake. But what intrigues me is that the lawsuit is claiming copyright infringement, not breach of contract. They are claiming they own a copyright on these bone casts.

As a general rule, you can't copyright a fact. The landmark case here is Feist v. Rural (1991), where the US Supreme Court held that a company could not claim copyright of its list of names and phone numbers. The particular medium, method of presentation, any commentary or editing - those can all be copyrighted as creative work. But the bare facts - the list of numbers - could not.

So can BHIGR claim that their bone casts are original, creative works? The president of the company, David Larson, claims that making dinosaur bone casts requires "a blend of scientific and artistic creativity," but otherwise emphasizes the amount of time and effort that they require. That smacks of the "sweat of the brow doctrine," which claims that amount of sheer labor that went into a production justifies the creator's monopoly over the product. That's an attractive, seemingly even a common sense, doctrine, especially to producers. But since Feist v. Rural, it's not the law in the US.

The pitfall for BHIGR is that the creativity lies mainly in their methods, not in the finished product. In fact, it's hard to imagine that they could be successful selling products they claimed were artistic representations of a dinosaur bone, rather than faithful and exacting reproductions of the original. Their website emphasizes, on the one hand, that "Perhaps the most important factors required in making fine molds and cast replicas are ingenuity and creativity." On the other hand, they also boast that they "have successfully developed new methods and materials for molding fossil specimens and producing cast replicas that retain the look and feel of the original fossils." That makes it sound like the value of the casts is not in their artistry, but in their adherence to fact.

I might be looking at this wrong. Perhaps the best example is a photograph of a building: you can still copyright the photograph, even though it's a representation of an uncopyrightable fact. If so, I look forward to the ruling setting me straight.

[Post script] It occurs to me that another comparison that might work in BHIGR's favor would be translations of old texts, which are original works for copyright purposes. Thus the New International Version translation of the Bible is under full copyright, despite the great age of the Bible itself. The 400-year-old King James Version, of course, is in the public domain.]

Labels:

copyright,

intellectual property,

law

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Why tonight?

We're expecting snow tonight, which should have me in great cheer, snow-lover that I am and all. Yet ... yet ... it's the first lunar eclipse to fall on the winter solstice in some 500 years and it's not likely that I'll get to see any of it. But I don't have to work tomorrow so I just might stay up until 3:00, just in case.

We're expecting snow tonight, which should have me in great cheer, snow-lover that I am and all. Yet ... yet ... it's the first lunar eclipse to fall on the winter solstice in some 500 years and it's not likely that I'll get to see any of it. But I don't have to work tomorrow so I just might stay up until 3:00, just in case.

(The good folks at the BBC will surely be embarrassed to realize they've called the winter solstice the longest day of the year. That would be the longest night of the year, of course, with the exception of Christmas Eve for children.)

Labels:

nature

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, December 17, 2010

Friday photo

Whee! Winter has arrived in southeast Michigan, snowy and cold as God intended it. Now if we can only get still more snow, and maybe have steam rising out of the ground to coat the trees with ice, it would look as wintry as Yellowstone.

Labels:

photography,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Where have all the colors gone?

Finals are over and it's slow on the desk, so I'm playing with Google's latest toy: the Google Books Ngram Viewer. You can graph the usage of words found in Google's collection of scanned books, one at a time, or comparing one phrase against another. It's quite addictive.

But here's a weird trend that I found. If you search for simple words, there's a tendency for their frequency to drop somewhere around 1950, and then begin rising again in the 1990's. Here's a graph of the words blue, red, green, and yellow between 1900 and 2008. Each of them shows this same patter. (I've cleverly arranged for each word to show up in its proper color so that you don't have to read the tiny text)

Other common words show the same thing. For example, man, boy, and girl show that same dip and recovery. Woman appears to start down the same path, and then gets a sudden boost in the mid-1960's. (Damn you, Betty Friedan, for messing with my data!)

Recall that the y-axis represents the frequency of these words compared to other words appearing in print. Did postwar publishing trend away from simpler terms (I mean, "eschew monosyllabary")? And what about the recent trend back upwards? There's been a boom in children's and young adult literature in the past decade or more, but would it make up such a large proportion of publishing as to explain why simpler words are becoming more common again? That's the best guess I have, but I'm none too confident in it. Ideas?

Labels:

information visualization,

language,

publishing

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

The Peculiar Institution - the South

Here's an interesting article in the NYT about a map showing slave populations in the South, compiled from the 1860 Census data - the high water mark for American slavery. And the last time a Census could even compile information on that particular demographic. Historian Susan Schulten notes,

The map uses what was then a new technique in statistical cartography: Each county not only displays its slave population numerically, but is shaded (the darker the shading, the higher the number of slaves) to visualize the concentration of slavery across the region. The counties along the Mississippi River and in coastal South Carolina are almost black, while Kentucky and the Appalachians are nearly white.

Translating numerical data into visual representations is one of the most powerful communication techniques available. The patterns just pop out at you. No wonder people were so taken with this map.

The presence of slavery, and (after 1865) large populations of African-Americans, wasn't the only thing peculiar about the South, though. There was a remarkable absence of foreign-born whites as well. Recently I was poring through the Statistical Atlas from the 12th Census of the United States -- that's from 1900, just to save you the arithmetic -- and came across this fascinating chart.

Click on the "Go to source" button to see it. The chart shows a breakdown of each state's population by race and origin. Four races are listed: Indians, Chinese & Japanese, Negro, and White (corresponding to the "Red and yellow, black and white" that I learned singing "Jesus Loves the Little Children" 'way back in Sunday School*). For whites, there are three further subdivisions: native white of native parents (baby blue), native white of foreign parents (pink), and foreign-born white (green). These were the categories that mattered in 1900.

Notice the states with the longest black lines - those are the Old South, the slave-holding South before the end of the Civil War, and the states that still held the majority of the nation's black population before the Great Migration. And in 1900, a period of intense immigration, most of those states had little to negligible pink and green in their bars. In other words, almost everyone who wasn't black was a white of at least the second generation. In a nation of immigrants, the South drew almost no immigrants.

According to the next couple of Censuses, little changed during the next 20 years. Bear in mind that this is one of the most immigration-heavy periods in US history. Yet the South missed it. They first developed enough of a separate identity to secede from the rest of the country, then learned to resent outsiders all the more intensely -- as you would, too, if you'd suffered invasion, defeat, and military occupation for a dozen years. And then they had the privilege, if privilege it is, of remaining insular while the rest of the country went through the wrenching experience of assimilating people who were as foreign as could be imagined (not only Chinese and Japanese, but Irish, Italians, Greeks, and so forth).

In respect to immigration and Americanism, it was even uglier 100 years ago than it is today. The "hyphenated American" (e.g., German-American) was no American at all, said Theodore Roosevelt, while Woodrow Wilson compared the hyphen to "a dagger that [the immigrant] is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic." The 1924 National Origins Act represented an unabashed attempt to keep the US not just white, but lily-white, by limiting the number of immigrants from unpopular nations.

The South didn't need the help, though. Aside from a few Yankee carpetbaggers, unwanted immigration wasn't part of their experience. Other people's families had been there just as long as yours and their brand of religion was probably the same as yours. No one had to accommodate diversity, when there were only two ethnic groups and their status was legally defined.

If it seems at times that Southern culture is especially prone to creating parochial mindsets, and people who steadfastly refuse to accept that not everyone thinks the same as they do -- and that is how Southern culture often comes across to me, at least as expressed in politics and the culture wars -- then maybe this is part of the reason why: no other region in the country was allowed to remain so culturally insular for so long a time.

______________________________________

* Which dates from about the same era, interestingly enough. This piano rendition renders the tune in fine 19th Century style.

Labels:

cartography,

history

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, December 10, 2010

Friday photo

Doublet Pool is one of the most attractive thermal features in the Upper Geyser Basin, if you find it - it's tucked away on Geyser Hill, across the Firehole River from the lodges, stores, and benches for viewing Old Faithful. I don't mean that it's really hidden away, but just that the folks who don't bother walking through the basin won't get to see it.

Doublet has been known to erupt slightly with a bit of bubbling, and on rare occasion even throw some water a couple feet in the air. Usually, though, it's just another of the steaming hot pools, with that clear blue (bacteria-free) water that the hottest pools have, and the red bacteria mats in the shallow areas where the water is merely warm and can sustain thermophilic life. It's called Doublet because there are two small pools connected by the narrow channel that you see in the photograph.

I don't entirely understand how the scalloped edges form. Silica is precipitating out of the water, slowly building up the mass on the sides of the pool. But why the round scallops? There's no sign of water draining into the pool and cutting channels; those would look like gullies instead of scallops, anyway. My best guess is that the edges begin jagged and random, but as the silica accumulates, it does so at equal distances around any pointed surface (recall that a circle is defined as the set of points equidistant from a given point). The tendency would be to grow the rounded scallops out from the edges of the wall and ever farther into the pool; pointy edges can't help being a passing phase. Or maybe there's some entirely different reason for that shape.

Labels:

photography,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Thursday, December 9, 2010

An English major finds a job!

Writing for the Colbert Report (jump to 3:20):

| The Colbert Report | Mon - Thurs 11:30pm / 10:30c | |||

| Tip/Wag - Art Edition - Brent Glass | ||||

| www.colbertnation.com | ||||

| ||||

Friday, December 3, 2010

Friday photo

Two weeks ago I posted a photo of the Old Faithful Inn, whose railings and faux supports are made of bare lodgepole pine logs. These were originally put in place with their bark intact, but the logs were "peeled" in 1940. Lo and behold, it was discovered that Nature had already decorated the beams with an intricate grooved tracery, courtesy of countless pine bark beetles. No one knew.

Similarly, the tree above has been scoured by beetles, whose action would have been invisible until the tree was killed during the 1988 North Fork fire. I have to admit, I don't understand why the outlines of the beetle trails are darkened, but not the interior or the rest of the tree. But it's an attractive arrangement nonetheless. Nature is an artist.

I doubt the patterns have as much mathematical structure as has been claimed for Jackson Pollock paintings (purportedly an intuitive application of fractal patterning), but that section to the left looks to me almost like a form of writing, perhaps the sort of thing that Mayan glyphs might have evolved into over time.

By the way, leaning into a tree while standing on a 30-degree slope on skis is not the easiest way to get a sharp photograph. So I'm a bit proud of that.

Labels:

art,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, November 26, 2010

Friday photo

Some messages are just meant to be kept in-house.

I'm offline most of the week, so nothing wordy today. Happy Thanksgiving!

Labels:

humor

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, November 19, 2010

Friday photo

In 2004, Yellowstone celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Old Faithful Inn, an originally quaint, now Byzantine wooden hotel that sits exactly one eighth of a mile from Old Faithful Geyser. Begun in the summer of 1903, construction was finished in time for the Inn to open the following season and it has been one of the most famous buildings in the West ever since.

That precise distance from Old Faithful Geyser is no accident. It was as close to the geyser as they could legally build. However, one notable, if often overlooked, feature of the Inn is that it is aligned to direct visitors' attention away from the geyser and toward the rest of the geyser basin. If you stand outside the front door, or lounge on the observation deck above the porte-cochere, you have to make a 90 degree turn to the right in order to look at the geyser. Looking straight out presents you instead with an invitation to discover the rest of the amazing Upper Geyser Basin, full of wonders such as Castle Geyser, Grand Geyser, Morning Glory Pool, and -- not the best, but my favorite name -- Spasmodic Geyser. If you come to the Inn and don't discover there's more to Old Faithful than Old Faithful Geyser, it's your own danged fault.

Unfortunately, the two huge wings added to either side in 1913 and 1928 spoiled the balanced appearance that the Inn originally presented (as well as blocking the view of Old Faithful from the dining room). Besides sprawling like overturned tractor-trailers off both ends of the "Old House," they abandoned the log construction of the original, as well as the A-frame roofs.*

However, the interior is still a delight. What I like in this photo is the number of distinctive Inn features I was able to gather into a single image. The distinctive wooden supports, both in full view on the opposite side, and close up so as to show the beetle scorings that create the most incredibly artistic-yet-natural effect; the US flag hanging over the lobby; the old electric lights; and, for the anniversary season, the large banner suspended from the ceiling and one of the smaller banners hung from the balcony. I rather regret the speaker in the lower right corner, as well as the light coming in from the dining room, but otherwise I enjoy the harmonious composition. This is one of those photographs where I spent a good twenty minutes fussing because the tripod was six inches too far to the left, or had raised the camera four inches too high.

The immense open space in the Inn lobby has been known to scare the hell out of modern structural engineers who venture into the building. The supports in the upper reaches look, shall we say, spindly, and they all seem to run mainly lengthwise, implying that the seven-story roof has no cross support. Apparently, that support exists elsewhere and the building is safer than it looks, and considering that it has stood for over a hundred years in a seismically-active region, and, survived the 7.4 Hebgen Earthquake, it would have to be.** Nonetheless, the recent renovation project has addressed some of the structural concerns, as well as making many aesthetic alterations. I left Yellowstone just as they were beginning and haven't been back in the meantime, but you can learn about them here.

Further reading:

Quinn, Ruth. Weaver of Dreams: The Life and Architecture of Robert C. Reamer.

Reinhart, Karen Wildung, and Jeff Henry. Old Faithful Inn: Crown Jewel of National Park Lodges.

_________________________________

* The flatter roofs are much friendlier to the winterkeeper who has to go up remove the snow that the high-pitch roof is supposed to shed, but doesn't always. In the film version of The Shining, we're told that a winterkeeper has nothing to do but putter around and keep the heat running; the truth is, there can be some hard work involved.

**I have heard it claimed, albeit not directly from an expert, that this was mainly because of the luck that the ground wave was traveling from northwest to southeast; had it come from another direction, the Inn would probably have collapsed.

Labels:

photography,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Thursday, November 18, 2010

How to get on the wrong side of the internets, conclusion

Under a storm of negative publicity over acts of plagiarism and jaw-dropping ignorance of copyright law, Cook's Source magazine has been hounded into oblivion. Let that stand as two warnings: if you publish, you need a basic understanding of copyright; and, in the internet age, that presumed non-entity on the other end of your emails just might be able to conjure up a horde of rampaging barbarians faster than a Capital One commercial.

Labels:

commerce,

copyright,

publishing

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

Beautiful Mother Earth

From the USGS, The Earth as Art:

This is the Dasht-e Kevir, the Great Salt Desert in Iran. Mostly uninhabited, for the same reasons that the Mormons stopped when they reached the Great Salt Lake and didn't continue on to the Bonneville Salt Flats.

The whole display consists of 41 LANDSAT 7 images, selected for their aesthetic qualities rather than for their informational value. Some of the colors will look unnatural, as LANDSAT captures images in a variety of wavelengths of the visible and infrared spectra. My favorites are those that don't get too radical with the coloring, but your tastes may vary (i.e., be wrong).

And if you like these, you'll want to check out the sequels, Earth as Art 2 and Earth as Art 3.

Labels:

art,

cartography,

photography,

science

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Irony, or Why I don't take conservatives seriously, pt. DCCXIII

Republican Andy Harris, an anesthesiologist who defeated freshman Democrat Frank Kratovil on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, reacted incredulously when informed that federal law mandated that his government-subsidized health care policy would take effect on Feb. 1 – 28 days after his Jan. 3rd swearing-in.

(snip)

“Harris then asked if he could purchase insurance from the government to cover the gap,” added the aide, who was struck by the similarity to Harris’s request and the public option he denounced as a gateway to socialized medicine.

Understood properly, however, Mr. Harris isn't really being the hypocrite he appears to be. Conservative hostility to health care reform never rested on fiscal concerns. It all comes down to the most fundamental dichotomy of conservative thought: their self-image of themselves as responsible, hard-working producers v. lazy, irresponsible parasites (aka "liberals"). It's why Social Security and Medicare remain untouchable, while health care reform was frequently opposed on the grounds that it would offer benefits to illegal immigrants (surely the most trivial of concerns regarding the financing of health care reform).

Mr. Harris is hard working and responsible. He deserve health care, and he deserves it now. I won't quibble with that. I just wish he would consider that he might not be the only one.

Via The Daily Dish

Labels:

health care,

politics

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, November 12, 2010

Friday photo

I'll give you a second to figure out what's going on with this photograph. I did introduce a little digital noise, to give it a grainy look, and removed the color. But all that fuzziness and squiggly contours in the trees are entirely natural - no filters, no Photoshop work.

The trick is to realize that the photo is upside down. This is a reflection in the lake, a lake that was quite calm but supplied just enough ripples to distort the image of the shoreline. I just love the effect, especially the blurred distant forest on the left side.

Labels:

photography,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Dead to irony

These days, I spend so much time rolling my eyes that I'm afraid the optic nerves are going to tangle into a knot. This appeared in The Watchtower:

Yes, the Jehovah's Witnesses are complaining about people who won't keep their opinions to themselves. But I suppose they are the experts on that subject.

Via The Friendly Atheist

Labels:

religion

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Saturday, November 6, 2010

How to get on the wrong side of the internets

Apparently this story is making the rounds and now an ignorant, arrogant, unscrupulous small time publisher has learned two things about the internet that anyone in her position should already have known:

Update: The slapdown was immense, probably more than was at all necessary. Still, this made me laugh:

The company said it shut down its Facebook page on November 4, but it has since been hacked and is no longer controlled by Cooks Source. Ironically, the publication complained about the hackers who are posting items to its Facebook page "without our knowledge or consent" and posted a link to a Facebook tutorial about how to report claims of intellectual property infringement.

Labels:

copyright,

publishing

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

You'd mock Charles Dickens for this ....

... but the Vice-President of the American Forest Resource Council is named Ann Forest Burns.

Via James Fallows

Labels:

humor

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, November 5, 2010

Friday photo

You might have to look at this photo for a moment before you figure out what it is, but that is an underside view of snowpack sliding off a roof. That's in slow motion, of course - the snow wasn't visibly moving when I took the photo. You could almost call it glacial speed, except it's certainly quicker than most glaciers move.

The dorm has a metal roof, which helps remove the snow by providing a slippery surface when there's a little bit of melt. It reminds me of earthquakes, actually, because the forces build up invisibly and then release their energy with no warning. The snow sits on the roof quietly, and then suddenly the friction can no longer hold the weight; you hear a sudden soft rumbling as a strip of snow slides down the roof and then a whump whump whump as it all falls to the ground.

But as I said, the snow in the photo wasn't moving that fast. This is a porch roof on the north side of the dorm and it doesn't get much sun. It's also smaller, so there's less weight pushing the snow downhill and it just creeps slowly instead of sliding off in a rush.

It looks like about a foot of snow slid off the roof during the day, halted when the temperature dropped, and began again the following day, when I took the photo. But during the night, the weight of the overhang was just enough to bend it downward without breaking off, leaving an unconformity of sorts that's obvious because of the way the roof structure leaves grooves in the snow. Would have been cool to have a time-lapse video of the process, but it's also just as cool to see the effects frozen (heh heh) in place.

You can see a couple more photos of sliding ice and snow here. I think I like these because of their similarity to geological and evolutionary processes: always at work, but only visible after a certain amount of time has passed.

Labels:

nature,

photography

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

Friday, October 29, 2010

Friday photo

Colter Bay is, of course, named for the famous mountain man John Colter, who is suspected to be the first white man to visit Yellowstone. We're not sure -- it seems pretty certain that he traveled through Yellowstone, but there's every chance that some French or Spanish explorer might have been there shortly before him, without leaving a record.

Colter was on his way back to St. Louis with Lewis and Clark when he met up with a pair of trappers; with his commanders' permission, he left the expedition and went with his new partners. That venture didn't work out, but he met up with Manuel Lisa of the Missouri Fur Company and decided to try the trading business again. It was while employed by Lisa that Colter made his journey through the northern Rockies, locating native bands and trying to persuade them to conduct business with the Missouri Co. This was in the fall and winter of 1807-08.

A few years after this trek, Colter met up with William Clark again and the two discussed his travels. Almost all we know of Colter's route is all based on this notation in the map Clark was compiling of the West:

Remember that Clark and Lewis had taken careful observations of the route of the Missouri River; it's very accurate on the map, as are the locations of its major tributaries. Lisa's fort was at the mouth of the Bighorn River, near present-day Hardin, Montana, and Colter seems to have ascended the Bighorn, turned west at the Shoshone River, and probably reached present-day Cody. Clark's map indicated "Boiling Springs" there, and although the hot springs around Cody are no longer active, there are other contemporary accounts of them; in all probability, this was the site referred to as "Colter's Hell," a name that was later - and erroneously - applied to Yellowstone itself.

That much is pretty clear from Clark's map, but after that it gets murky. Clark was filling in areas based on verbal reports, without the benefit of systematic surveys, and the results are rather imprecise, to say the least. But his map does contain two lakes, which he named "Eustis" and "Biddle." And it just happens that this area, in reality, contains two of the most prominent lakes in the Northern Rockies: Lake Yellowstone and Jackson Lake. Anchoring a reconstruction around these two landmarks, it's possible to make a plausible guess where Colter went.*

It's been proposed that he crossed over Togwootee Pass into Jackson Hole, but the map shows him skirting well south of Jackson Lake; therefore, it seems more likely that he made the difficult passage over the Wind River Range via Union Pass, between present-day Dubois and Pinedale. If that's the case, then he probably followed the Hoback River up into the south end of Jackson Hole.

It's pretty well accepted that he crossed the Tetons, probably at Teton Pass between Wilson, WY, and Victor, ID, and went north through the flat valley west of the Teton Range. The approach to "Lake Biddle" from the northwest would suggest that he crossed the northern end of the Tetons and encountered Jackson Lake for the first time.

From there, he apparently went north and found Yellowstone Lake, although it seems odd that the Snake River should be shown so truncated - it would have been the logical route all the way up to Lewis Lake or beyond. Then along the western shore of Yellowstone Lake and up the Yellowstone River - except now there are a couple more problems. The major discrepancy is that the outlet to the lake is shown to the southeast, almost 180 degrees opposite of reality. It's hard to account for an error that large, since nothing about the geography would suggest that Yellowstone Lake drains from anywhere but its northern end. Perhaps Clark simply misunderstood what he was being told.

Second, it seems surprising that Colter traveled along the west side of Yellowstone Lake without noticing the West Thumb thermal area. It would also be weird if he saw them, but didn't find them as worthy of mention as the "Boiling Springs" near Cody. Of the two possibilities, the former seems more explicable to me.

For the rest of the route, Colter is presumed to have reached Soda Butte Creek via the Lamar River, and thence to Clark's Fork and back to the Yellowstone, perhaps near Laurel. Again, it's awfully hard to make sense of Clark's map on this point. He shows Colter descending the left bank of the Yellowstone, then crossing it and, instead of following a tributary (as the Lamar is), crossing a divide into a parallel river basin. But there's really no better way of getting from Yellowstone Lake to Pryor's Fork than that, and it's pretty solid that he did travel between those two places.

If this reconstruction is accurate, this would be the approximate route that Colter took:

View Colter's route? in a larger map

_________________________________

*My description is largely based on the description in Mattes, Merrill J. "Behind the Legend of Colter's Hell: The Early Exploration of Yellowstone National Park," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Sep., 1949), p. 254.

Labels:

history,

photography,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

Larison on historic causality

This post by Daniel Larison is worth reading, primarily for this paragraph:

A less obvious, but no less important reason I am discussing this at length is that I have no patience with historical arguments that stress broad, sweeping cultural and/or religious factors at the expense of discernible, specific causes. That partly informs my impatience with claims that jihadists attack Western governments because of “who we are” rather than what those governments do. When we want to avoid understanding the realities of terrorism, we simply say, “Their god compels them,” and leave it at that. What is most bothersome about this is that it doesn’t actually take cultural and religious factors seriously at all. On the contrary, it ignores the actual significance of cultural and religious factors by distorting them beyond recognition and using them as the framing for essentialist arguments that are designed to perpetuate conflict and facilitate vilification of other peoples. Such arguments pretend to pay attention to deeper causes, but in the end provide the most superficial analysis dressed up in condescending rhetoric. Instead of explaining a phenomenon, they are intended to explain it away. [Emphasis added]

One of the more important books I ever read - and I didn't appreciate that fact until some time had passed - was James P. Ronda's Lewis and Clark Among the Indians. If you haven't read it, do. Ronda traces the Corps of Discovery's famous trip from St. Louis to the mouth of the Columbia and back by recounting their encounters with the natives, explaining how Lewis and Clark misunderstood the Indians at every step of the way. That might sound like a writer scoring cheap and easy points off the stupid white guys, but it's a more subtle book than that.

Lewis and Clark - Lewis, especially - are considered pretty good ethnographers for their day, taking careful notes on the people they met, generally with more description than moralizing. As with their natural science notes, they are valuable records to this day. But everything they saw was filtered through their own agenda, which was to get all of the Plains tribes to quit fighting each other and direct all their trade to the Americans. The Indians, surprisingly enough, had their own agendas and explaining these, with the benefit of an extra 180 years of scholarship, is what Ronda is about.

And what emerges is not a race of people who fail to measure up to Americans, nor a race of noble savages who stand as a rebuke to the benighted white men, nor self-contained cultures that are forever inexplicable to outsiders. You get people, people who may have different beliefs and customs, but are not really as different as they seem at first. You have Arikaras reeling from a smallpox holocaust, with the survivors trying to recreate a viable community from the remnants of rival groups; Lakota men using a confrontation with the Corps of Discovery to posture for status in front of their peers; Shoshones who were willing to help the Americans, but didn't believe they could afford to give as much as was being asked; savvy Chinooks and Clatsops who had long experience trading with British ships and turned the tables on the Americans by driving hard bargains for food and boats.

Even the stranger cultural practices come to make sense. Lewis and Clark had no idea why Mandan men were so generous in giving their wives to the Americans for one night stands, to the delight of enlisted men. What they didn't realize was that Mandans believed skills and powers could be transferred through shared sexual partners; when they saw fifty Americans, with their boats full of guns and trade goods, they assumed "These guys sure have some powers. Maybe we can get some of that to rub off on us." A strange belief, to us, but a perfectly rational action for such believers to take.

In a similar vein, it's really not so hard to understand why someone might decided to wage war on a rich, arrogant, and overbearing country, especially if they have soldiers occupying your country. What's hard to understand is why anyone finds this hard to understand.

Red in tooth and claw

This scary photo of a grizzly bear chasing down a badly-mauled bison was taken early last April in Yellowstone:

This probably wouldn't happen at any other time of the year. April is a nasty month for herbivores, when the grass is barely starting to reappear and they're at the end of the fat reserves they piled on the summer before. A bison at full strength is too dangerous for even a grizzly bear to want to tackle, but this cow looks pretty thin. Even at that, it's uncommon for the bear to want to take down a large live animal - there's normally a good amount of winterkill lying about that he could have scavenged much easier.

[Update: I've learned that this photo was a winner in the Co-op Recreation photo contest this year, and was taken by an employee at the Old Faithful Post Office].

Labels:

wildlife,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

Misinformation

I'm convinced: I don't want Obama beans up my nose!

Saturday, October 23, 2010

Big claims

A funny little incident occurred this week when the organization that manages English historic sites claimed copyright over every image ever taken of Stonehenge. According to the blog of the image library fotoLibra, the organization English Heritage sent them the following message:

We are sending you an email regarding images of Stonehenge in your fotoLibra website. Please be aware that any images of Stonehenge can not be used for any commercial interest, all commercial interest to sell images must be directed to English Heritage.

As of Friday, the English Heritage site has posted a disavowal:

English Heritage looks after Stonehenge on behalf of the nation. But we do not control the copyright of all images of Stonehenge. And we have never tried to do so. We have no problem with photographers sharing images of Stonehenge on Flickr and similar not-for-profit image websites. We encourage visitors to the monument to take their own photographs.

If a commercial photographer enters the land within our care with the intention of taking a photograph of the monument for financial gain, we ask that they pay a fee and abide by certain conditions. English Heritage is a non-profit making organisation and this fee helps preserve and protect Stonehenge for the benefit of future generations. The majority of commercial photographers respect this position and normally request permission in advance of visiting. We regret the confusion caused by a recent email sent to a picture library.

Which doesn't quite explain why the original email went out in the first place. I wonder if some mid-level executive has been reading about expansive copyright claims and just assumed he had the law on his side?

Labels:

copyright

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, October 22, 2010

Friday photo

Okay, so everyplace has to have an "Inspiration Point," surely the least inspired place name in the English-speaking world next to "Main Street." It's still worth taking a look at Bryce Canyon. The Paiutes were purportedly inspired to imagine a bunch of people turned to stone; the Mormon settler Ebenezer Bryce was inspired to the hilariously prosaic, "It's a hell of a place to lose a cow."

Bryce Canyon isn't really a canyon -- it's the side of a cliff being eroded away. You might think - it being in the middle of a desert and all - that the hoodoos are created by wind erosion rather than water. This turns out to be wrong; it's all about water. Not a single stream, as canyons are generally carved, but innumerable rivulets formed from a bit of rain and melting snow, with the extra power of an almost year-round freezing and thawing.* On the top of each spire -- or hoodoo -- is a layer of relatively hard rock that doesn't erode away too easily. But once the water works its way through some cracks and reaches the softer rock underneath, it begins to carry away the soft stuff while leaving the hard rock behind. Since the wind isn't doing much of the work at Bryce, all the erosive action is at ground level -- which is why the upper parts of the hoodoos stay put, while the spaces between them just get deeper and deeper.

Utah is full of weird scenery, so weird that it inspired the alien scenery of Calvin & Hobbes. Here's how Bill Watterson described his Spaceman Spiff stories:

The Spiff strips are limited in narrative potential, but I keep doing them because they're so much fun to draw. The planets and monsters offer great visual possibilities, especially in the Sunday strips. Most of the alien landscapes come from the canyons and deserts of southern Utah, a place more weird and spectacular than anything I'd previously been able to make up. The landscapes have become a significant part of the Spaceman Spiff sequences, and I often write the strip around the topography I feel like drawing.**But even by Utah standards, Bryce is one weird-looking place.

______________________________________

* Being at high altitude, but mid-latitude, the sun will easily melt much of the snow in the winter, while the temperature also dips below freezing on most summer nights.

** Watterson, The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book, 1995.

Labels:

nature,

photography,

the West

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

San Francisco, 1906

If you didn't catch 60 Minutes Sunday night, you should definitely check out this story on a mysterious film of San Francisco, taken from a cable car moving down Market Street, near the turn of the century. It's an intriguing film in itself, catching a (mostly) candid view of the city in a past era. But it grows even more meaningful when an archivist's careful research discovers it was taken on the eve of the disastrous 1906 earthquake.

The other Art of the Possible

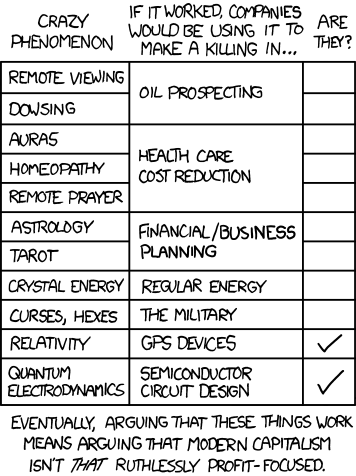

xkcd offers another way to spot BS:

Labels:

belief,

technology

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Friday, October 15, 2010

Friday photo

Nothing much to say, other than that I like reflections.

Labels:

photography

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Thursday, October 14, 2010

Making a flat earth rugged

I'm trying to figure out how long this feature has been a part of Google Earth: when you pan a mountainous scene back and forth, you can see it in three dimensions. I'm pretty sure it wasn't always there, but I've been mostly working in the relatively flat Midwest and didn't notice it until now.

You can see it for yourself by zooming in on any mountainous area, or you can download this file and open it directly in Google Earth to find the location seen here:

What you're looking at is Dome Mountain, a prominent peak at the exit to Yankee Jim Canyon, north of Yellowstone National Park. If you use the right and left arrow keys to pan back and forth, you'll suddenly start seeing the landscape in three dimensions. As soon as you stop, it's flat again.

To do this, Google Earth has to continuously distort the image as you pan. The parts of the image that represent the highest elevation are stretched farther toward the edges of the screen, while the lower elevations stay relatively still. As you'll immediately recognize, this is how you experience the real world: when you move, objects that are close to you seem to change position much more than do those farther away.

I underestimated the amount of distortion, until I compared snapshots of the mountain at the extreme sides of the screen. Here I've placed identical circles at the same point in each one, to make for easier comparison. When the mountain is moved to the left (as if you were viewing slightly from the east), see how much more area the east side of the slope seems to take up. In the image to the right (corresponding to a vantage point slightly more to the west) it's the western side that seems very wide and the eastern slope that is narrowed. Notice the treeless, gullied area on the western slope, which is rendered perhaps twice as wide in the right hand shot as it is on the left.

Keep in mind that Google doesn't have multiple views available. It's all the same flat, 2-dimensional image that is being manipulated in just the right manner to mimic what you'd see if it really were 3-D. Through long experience with the real world, your visual system has learned that close things shift position more noticeably than distant things do, so it can be tricked into thinking you're seeing depth, even when you aren't. Google falsifies the image so that your brain falsely interprets what's really in front of your eyes - all to give you a truer impression of what you'd see if you really were floating above the mountain. Cute trick.

Labels:

cartography,

information visualization

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Sunday, October 10, 2010

Barack X?

Here is why Poe's Law is true. A blogger calls for testing Obama's DNA and one of the commenters is insisting that the President is the secret love child of Malcolm X. Because someone that evil couldn't be the spawn of just anyone, could he?

Friday, October 8, 2010

Friday photo

American Black Bear. Yellowstone National Park, June 2004.

American Black Bear. Yellowstone National Park, June 2004.Here's a little black bear that I found browsing the road side near Abiathar Peak one day. Although I kept all the commotion out of the photograph, the bear was nearly surrounded by a crowd of tourists and parked cars. However, he paid them no mind and I almost have to admire how well he maintained his concentration with all the ruckus going on. A true Zen master.

How different his behavior would have been fifty years ago! Bears didn't ignore cars then; they sought them out, like a child chasing an ice cream truck. Cars meant handouts of food and the best thing to do with one was to stand up and stick your nose through the window. If there was anything in Yellowstone more iconic than Old Faithful, it was the begging bears along the roads.

By the time the National Park Service arrived in Yellowstone (in 1916) to take over management, there was a long history of feeding bears to provide entertainment to tourists. Fenced-in feeding areas, some of them even equipped with grandstands, were common in the campgrounds, and shows were scheduled every evening. Tourists could check out the schedule; the bears had it memorized.

The new NPS regime didn't change anything right away. Horace Albright, the Superintendent through the 1920's, had been one of the principle men fighting to establish the Park Service and had long experience in defending the national parks from ranchers, miners, loggers, and their allies in Congress (mostly scrupulous, although not entirely, Albright was undoubtedly one of the great bureaucratic operatives of his day).

With that kind of experience, Albright was keen to make the parks as visitor-friendly as he could, albeit without compromising their natural values. He would have nixed carnival rides, but he saw nothing wrong with allowing, or encouraging, the animals to entertain the tourists. In fact, he was known to stage buffalo stampedes for VIP's. Oh, that's him on the left, smiling as the bears crawl over his table and eat off the plates.

With that kind of experience, Albright was keen to make the parks as visitor-friendly as he could, albeit without compromising their natural values. He would have nixed carnival rides, but he saw nothing wrong with allowing, or encouraging, the animals to entertain the tourists. In fact, he was known to stage buffalo stampedes for VIP's. Oh, that's him on the left, smiling as the bears crawl over his table and eat off the plates.By the time Albright left the Park Service in 1933, attitudes were changing about what was "natural" or appropriate in a national park. Younger wildlife managers wanted to see more natural behavior, more natural processes, to rewild the parks which -- wild as they appeared to a city slicker -- seemed uncomfortably carnival-like to the younger mindset.

Rewilding the bears took years - decades, even. The campground feeding shows ended after 1942, but the bears were still everywhere. They didn't fear the humans, nor did the humans fear them(keep in mind, we're talking about black bears, not grizzlies). One elderly former "savage,"* a waitress at Old Faithful Lodge in 1950, told me there were bears all over Old Faithful in her day and insisted, "I was never afraid." She even swore to me that she once stepped on a bear while sneaking out the window of her dorm room one night to go drinking in West Yellowstone.

Nothing like that happens today. In six seasons at Old Faithful, I never saw a black bear strolling through the basin during the tourist season, not even on burger day in the EDR, when the aroma must have been detectable for miles. Intensive behavioral modification techniques -- mostly on the bears, but somewhat for the visitors, too (referred to, variously, as education or citations) -- brought an end to the era of begging bears. The bears of old would have been astonished at the young cub near Abiathar Peak, who had an entire line of cars all to himself and no idea what to do with them. Albright might have been reassured that tourists would still love his national parks, even without the beggars by the road.

__________________________________

* Park employees were known as savages, a term that came into use sometime before 1900 and persisted until about 1980. An entire Park vocabulary, often quite colorful, has regrettably disappeared. I may have to do a post on that someday, but in the meantime I'll leave you to puzzle out what stuffing dudes referred to.

Labels:

history,

wildlife,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, October 6, 2010

Ptolemy's map of Germany

An interesting article from Der Spiegel, the popular German news magazine. Go ahead, follow the link - this is the English language version.

It seems that a team of researchers has solved a long-standing puzzle: locating the settlements that Ptolemy, working around 150 C.E., listed with his map of Germany. Unfortunately, the article isn't terribly clear about it, but it appears that he drew rivers and mountains on his map, but listed the settlements separately in a table, with an idiosyncratic way of designating latitude and longitude. If I understand it correctly, it's this system that has resisted deciphering in the present day. However, the group of scholars has decoded Ptolemy's system in a way that matches up not only with many existing cities, but with known archaeological sites as well. If they're right, it would appear that Germany during the Roman Empire was a more heavily populated and cultured place than the Romans reported.

Labels:

cartography,

history

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Strange job description

From the Bozeman Daily Chronicle:

"High-raking park official to take Yellowstone reins in 2011"

Which is peculiar, because most of the trees in Yellowstone -- especially at the higher elevations -- are lodgepole pine, which don't drop leaves.

[Update 10/7: the typo has been fixed. Where's the fun in that?]

Labels:

humor,

Yellowstone

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Reading topo maps

If you, or anyone you know, have trouble reading topographic maps, if you just can't make sense of those contour lines and marvel that anyone could read the shape of the land based on all those squiggles -- here's a fine exercise for you.

Check out the New Zealand Topographic Maps, an excellent interface featuring topographic maps overlaid on a Google Maps base. If you select the "Terrain" option, the underlying map will switch to shaded relief, a portrayal that's less precise than contour lines, but gives an easy-to-interpret sense of the shape of the landscape. By moving the slider back and forth, you can adjust the transparency of the overlying topo map and switch seamlessly between the shaded relief and the contour lines. Try it out!

(Also, zoom in on some of those coast lines and note how accurately the topo maps fit with the satellite image. I was impressed.)

Labels:

cartography

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Where baseball comes from?

Here's an interesting post at Got Medieval about an early -- early early early -- version of baseball.

If you read to the end, you'll be rewarded with monkeys.

Monday, October 4, 2010

You want to go where?

Tourist site for Quebec City.

If you were pitching your city on the basis of "unparalleled romance," would you at the same time list HP Lovecraft as a reference?

Labels:

humor

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Friday photo (special Thursday edition)

(Be sure to click on the image for the enlarged version)

And Mercury is an unusual sight, even if the moon weren't so close by*. Most folks will never glimpse it -- not knowingly anyway. Being closer to the sun than Earth, it can only appear at sunrise or sunset, like Venus does, but it's so much closer to the sun that it's usually much harder to spot. It needs to be well out to the side, as seen from Earth, or it's overwhelmed in the sun's glare. Also, if its path around the sun - the ecliptic - is parallel to Earth's horizon, then it will rise at the same time as the sun and again the sky is too light. The best viewing is in the early spring or early autumn, when the ecliptic is more vertical to our horizon. This allows Mercury to rise higher before sunrise, or set later after sunset, when the sky is slightly dimmer, like so:

t also happens that Mercury is most visible when it's on the opposite side of the sun from Earth, even though it's farther away then. Otherwise, even though it's closer, it presents mostly its dark side to the world -- much like the moon in the photo, or a Goth chick.

* "Close by," of course, as viewed from Earth. The planet was actually 500 times farther away than the moon was.

Labels:

photography,

science

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

On the revolutionary(?) power of social networking

Malcolm Gladwell has a thought-provoking article at the New Yorker, entitled "Small Change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted."

The upshot: social networking fosters many weak ties, with weak enthusiasm and commitment. Comparing that to the tightly-organized civil rights movement, he argues against the ability of Twitter networks to create revolutionary change.

Labels:

culture,

technology

By

Scott Hanley

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

Book review: American Insurgents, American Patriots

Ah, the American Revolution. The King was a tyrant so the colonists rebelled - it's as simple as that, isn't it? If you're not sure, just see what Schoolhouse Rock had to say about it. It's not too different from what my 6th grade teacher taught me.

Ah, but then you make the mistake of going to college, taking a history class or two, and it all gets more complicated. The taxes weren't that high, the colonists seem to have never felt prouder of the British Empire than they did in the 1760's, and the complaints mostly came from a handful of merchants in just one city. How did that turn into a wholesale revolution?

John Adams famously commented, "But what do we mean by the American Revolution? Do we mean the American war? The Revolution was effected before the war commenced. The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people."  TH Breen's latest book, American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People, addresses both how and when that happened.

TH Breen's latest book, American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People, addresses both how and when that happened.

In Breen's view, the revolution is not a steadily-rising tide of resistance as it's usually portrayed, from the Stamp Act crisis, through the Tea Party, and culminating in the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Instead, there was a particular revolutionary moment, and it occurred in 1774 when the British government reacted to the Boston Tea Party by imposing the Coercive Acts, designed to harshly punish the entire city of Boston.

The Coercive Acts were indeed dramatic. First, they reorganized the governor's Council and filling it with royal appointees, where before the democratically-elected Assembly had the councilors. Parliament judged that there was too much democracy in Boston and they intended to correct the imbalance.

More punitive yet, they closed Boston Harbor to all commercial traffic until the East India Company was compensated for the vandalism. This not only attacked merchants like John Hancock, but guaranteed economic distress among the poorer classes who worked on the wharves. Everyone would suffer until everyone had submitted.

And to enforce it all, the navy arrived to blockade the harbor, unloaded three thousand British troops in the city, and replaced the governor with a military commander. After eight years of negotiation and appeasement, Parliament had decided that the time for patience was over, and this time they would teach the colonists a hard lesson in obedience. The decision was disastrous.

The British believed that the loyal populace - surely the majority of the colonists? - would take courage from the invigorated royal presence and turn against that handful of noisy agitators who had gotten then all into such trouble. Wrong, utterly wrong. In the modern parlance, the battle for hearts and minds was over and the British had just lost, decisively and irrevocably. To the waverers who might have thought cries of Tyranny! were overblown, there was no longer any doubt. No, it was all true: Parliament had sent an army to wage war on Americans and intended to grind them into poverty and deny them the self-government they were accustomed to. Fear and anger overwhelmed the common folks outside Boston, who had until now been more spectators to the crisis. Almost overnight they became revolutionaries - or, Breen now calls them, insurgents. The moderates were suddenly radicalized.

The fear spread to the other colonies at the beginning of September that same year of 1774, when a strange event happened. Rumors began to fly around Massachusetts and Connecticut that the British navy had bombarded Boston, then landed and burned the entire city. They hadn't, but thousands of farmers and townsmen in New England grabbed up whatever guns they had and began marching toward Boston to exact revenge, before learning the truth and turning back.

The first consequence was that mob of farmers and townspeople - the folks who would come to style themselves Minutemen - had proven to themselves that they would really turn out in the event of war. Until then, they had been full of talk, but who knew how many of these braggarts would actually risk their lives if the British army began shooting? Now they knew: perhaps more than 20,000 had grabbed their guns and begun to march, easily enough to overwhelm Gage and his men. No matter that they had responded to a false alarm - they had responded, when the danger seemed extreme. Their pride, confidence, and radicalism soared.

But it also just happened that a first Continental Congress was gathering in Philadelphia right when the hysteria broke, and this had a strong effect in rallying the other colonies to Massachusetts's side. In the aftermath of the horror they had felt at believing the British army was killing people in Boston, the delegates voted to support the Suffolk Resolves, an appeal from a rather ordinary town in Massachusetts that called for the colonists to stop cooperating with the British government and to boycott all commerce with Great Britain. The members of this Congress were still rattled, but they also saw how inflamed the rest of the public was. In fact, the "leaders" of the resistance were now scrambling to stay in front of the mob.

At this point, a local resistance movement an intercolonial rebellion. The Continental Congress called for the total boycott and recommended that all communities set up a committee to enforce it. Breen loves these committees, because they made the Revolution a creative event and not just a destructive one. The rebels could retain their attachment to law and order, even as they removed the existing governmental structure by chasing away royal officials, and they could restrain mob violence and retain a fig leaf of due process, even as they enforced the revolution upon the unenthusiastic.

That due process was a bare cover for coercion, to be sure. The rebels tolerated no dissenting opinions or evasion of the boycott. Violators were likely to be called before the committee, or even visited by a mob of angry neighbors, and strongly urged to confess their error and recant. If they didn't, they could find themselves shunned by the rest of their community, perhaps wearing tar and feathers, or even having their house pulled down. Freedom of speech was not one of the revolutionary virtues in 1774. But two points bear emphasizing here.

One, these were neighbors, and violence was fairly uncommon, especially compared with other insurgencies and revolutions we know about. The patriots wanted reconciliation, harmony, and they wanted to control the message. All you had to do was go along: a full confession and apology would usually restore one to good graces. It was mainly outsiders (Scottish Presbyterian merchants, for example), former royal officials, or the most stubborn loyalists who received the rough treatment.

Second, I used the language of a religious inquisition. Breen doesn't use that terminology himself, but I don't think he would disagree with it, either. Many of the common people did understand their revolution in religious terms. Without reading Locke (and here I am returning to Breen's arguments), they believed their rights came from God himself. As a corollary, any government that would trample its citizens' rights had ceased to be godly and resisting tyranny was virtually a religious obligation. Just like religious authorities, the rebels wanted unanimity, or at least the public illusion of unanimity. And they had great success. The British hoped a majority of loyalists would stand up for the Empire; the rebels were out to prevent it and, whether or not they were more numerous (we don't really know), they were far more energetic than their opponents. For all practical purposes, the entire countryside really was on the side of the rebellion.

Despite their reliance on intimidation, the occasional use of tar and feathers, and even beatings and vandalism, the insurgents of 1774 managed to minimize mob violence, keep order, and maintain a functioning quasi-government in the midst of revolution. This is what Breen admires about the common people of the Revolution. He sees what so often happens in revolutions: unrestrained violence, endless cycles of recrimination, and the destruction of a previously-functioning society. The American patriots created, perhaps accidentally, new institutions that created more than was destroyed.*

Although Breen never references it, the American experience in Iraq and Afghanistan always hovers around this book, not least in the use of the word insurgents. In fact, from the title I expected a more revisionist book, one that applying theories of insurgency and counter-insurgency to understanding the Revolution. That's not what this book is, but the experience of the last eight years intrudes anyway, especially in the use of contemporary language such as "losing hearts and minds." In retrospect, one wonders whether the British could ever have reestablished control over the colonies, even if they succeeded in crushing Washington's army; they certainly could not afford to keep foreign mercenaries on permanent garrison from Massachusetts to South Carolina forever. We Americans like to boast of the long odds against us in the Revolution, but we've tried counter-insurgency from the other side, too, and it's harder than it looks. Killing enemy fighters and controlling the country are vastly different matters and I wonder if, had the American army dissolved at Valley Forge, the British would only have found themselves back in 1774 again.

_________________________________________

* Incidentally, Breen has compared our current Tea Partiers to their more orderly forebears and believes the latter were the better people.